Captain Marko Berberović

Marko Berberović (1862–1943), son of Captain Krsto, graduated as a long-distance captain in Trieste, in 1890. Decorated with the Order of Danilo I, he was sent by the Prince of Montenegro to serve the Tsar of All the Russias in Odessa, where he was swept into the Great War, the Russian Revolution, and the collapse of the empires. After a disastrous shipwreck in the Black Sea while commanding under the Soviet flag, Captain Marko retired from active duty and returned to Morinj in 1924.

Beginning from the end. November 16, 1922

The Volga shipwreck in the Black Sea

Two centuries of maritime history of the Berberović captains from Morinj came to an end in 1922, on the rocks of the Black Sea, when the ship commanded by Captain Marko Berberović was lost in waters that had seen generations of his ancestors transport goods toward Trieste. It was the collapse of the world of empires in which the Serbs of Boka Kotorska had once dominated maritime routes. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was gone; the Ottoman Sultan was gone; the Tsar of All the Russias was gone.

As Marko swam to safety — the last of his crew to abandon the sinking Volga — it was time to say farewell to a world that had vanished. With that vessel disappeared not only a ship, but an entire geopolitical and maritime order, as new powers emerged from the ruins of the old.

Continue reading →

The shipwreck of November 16

On 16 November 1922, during a storm, the cargo steamship Volga of the Black Sea–Azov Shipping Company ran onto rocks near Cape Doob (мыс Дооб) in the Black Sea and was wrecked. The vessel had been built in 1881 at a shipyard in Sevastopol by order of the Russian Society of Steam Navigation and Trade (РОПиТ / ROPiT).

At the time of the shipwreck, Marko Berberović was serving as captain of the Volga, a position he had held since 1910, when he was sent to Odessa, decorated with a medal by order of the Prince of Montenegro, to serve in the Imperial Russian Merchant Navy with the aim of acquiring experience and later returning to serve Montenegro. This return never became possible, as Europe and its seas were soon drawn into the turmoil of the First World War.

Cape Doob (мыс Дооб), the “Bermuda of the Black Sea”

Cape Doob (Russian: мыс Дооб) is one of the headlands that delimit Tsemes Bay (also Novorossiysk Bay) on the north-eastern Black Sea coast. The bay is navigable year-round, but it is also known for strong autumn and winter bora winds that can severely disrupt navigation. Tsemes Bay is explicitly described as being affected by bora winds, and Cape Doob is one of the bay’s boundaries.

The best-known modern disaster associated with these waters is the sinking of the passenger steamship SS Admiral Nakhimov. On the night of 31 August 1986, Admiral Nakhimov collided with the bulk carrier Pyotr Vasev in Tsemes Bay near Novorossiysk and sank within minutes, causing hundreds of fatalities.

A more recent and much smaller-scale episode is the stranded dry cargo ship Rio. During a strong storm in December 2018, the vessel ran aground near Kabardinka, in the Cape Doob area. Accounts note that the crew was not injured, and the ship remained on the shore for years, becoming a local landmark.

Why shipwrecks happen here

The recurring risk factor most often cited for this stretch of coast is the northeasterly bora: sudden, very strong winds in autumn and winter that can rapidly create hazardous sea states and disrupt maneuvering and port operations in and around Tsemes Bay.

Another contributing factor is simply traffic density: Novorossiysk is one of the major Black Sea ports, so more vessels routinely enter and leave the bay. In such a setting, severe weather, constrained waters near headlands, and the need to hold position or approach anchorage can combine into situations where groundings and collisions become more likely than in open sea.

Russian Underwater Cultural Heritage

Information on the steamship Volga and its final fate is reported in Register of Underwater Cultural Heritage Objects of Russia. Part I: The Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. This volume is a scientific reference work produced by the D. S. Likhachev Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. Its purpose is to document known underwater cultural heritage sites within Russian territorial waters, based on archival research, historical literature, official reports, and data from underwater archaeological expeditions, maritime authorities, museums, and specialized organizations. The register includes shipwrecks, submerged structures, and other objects of historical significance, providing a consolidated reference framework for further research and protection efforts.

Sources: Bureau Veritas, Repertoire Général – General List of Merchant Shipping of All Nations: Steamers and Motor Vessels, 1914–1915, Paris, 1915 — link. Fleetphoto, Russian Vessel Database, Cargo steamer Volga (Волга), entry 112332 — link. Okorokov, A. V., Register of Underwater Cultural Heritage Objects of Russia. Part I: The Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, pages 228-229 (item 1073). Moscow: D. S. Likhachev Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage, 2016. (ISBN 978-5-86443-211-2)

A portrait of Captain Marko in Odessa (c.1910)

This portrait of Captain Marko Berberović was taken in Odessa by the photographer Ivan Antonopulo. Marko is wearing the uniform of an officer of the Imperial Russian Navy. On his chest are two decorations; the cross is the Order of Danilo I, awarded to him in 1903 by the Prince of Montenegro, shortly before he was sent to Odessa to serve in Russian maritime service.

Original photograph from the author’s private family collection.

Continue reading →

Ivan Antonovich Antonopulo, photographer in Odessa

The reverse of the photograph lists Antonopulo’s awards and distinctions and indicates the address of his studio on Deribasovskaya Street, Novikov’s House, one of the most prestigious photographic locations in Odessa at the time. No date is printed on the photograph; based on the decoration and uniform, it can be reasonably dated to the period 1903–1914.

Ivan Antonovich Antonopulo was one of the most prominent photographers active in Odessa from the early 1870s to the early 20th century. Having previously operated a photographic studio in Taganrog, he settled in Odessa in 1871, where he worked for more than three decades as a master of portrait and landscape photography. His studios were located at some of the city’s most central and prestigious addresses, including Deribasovskaya Street and later the Passage shopping complex, reflecting both his professional success and Odessa’s vibrant urban culture at the time.

Antonopulo’s work unfolded during a period when Odessa was a cosmopolitan port city of the Russian Empire, marked by intense cultural, commercial, and social exchange. His photographic output captured a broad cross-section of the city’s society: scientists, professors, athletes, artists, civic leaders, and ordinary citizens. Beyond portraiture, he produced extensive photographic views of Odessa’s streets, monuments, churches, harbors, and public spaces—many of which later served as the basis for postcards and illustrated publications documenting the city at the turn of the century.

Recognized during his lifetime with awards and honorary titles—including appointments connected to European royal courts—Antonopulo belonged to the generation of photographers who helped shape the visual memory of imperial Odessa. His legacy is particularly valuable today for reconstructing the appearance and atmosphere of the city before the upheavals of the 20th century. This historical overview is based on the research of Eva Krasnova and Anatoly Drozdovsky, local Odessa historians and collectors, whose work has been fundamental in documenting Antonopulo’s life and photographic heritage.

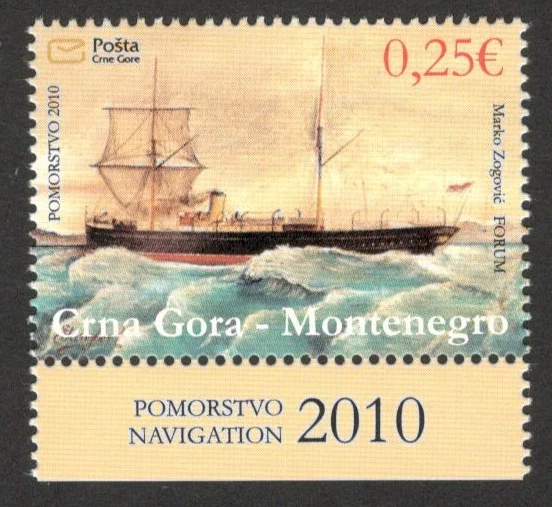

The first years at sea: the Yaroslav (1890-1895)

The first years at sea of Captain Marko Berberović were spent aboard the steamship Yaroslav, where he served as First Officer. An informative historical overview of the circumstances that led Marko to serve on the Yaroslav was provided by Dim Dimych in an article published in 2016.

Continue reading →

The war with the Turks in 1877-1878

The struggle for access to the sea formed the political and symbolic background of Montenegro’s maritime ambitions. As Dr. A. V. Shcherbak wrote about the events of the 1877–1878 war with the Ottoman Empire:

“With the acquisition of Volovica, the Montenegrins effectively took possession of the sea. To mark such an important event—one that fulfilled a long-cherished dream of the Montenegrins—the Prince, despite his strong dislike of water, boarded a boat with Colonel Bogolyubov and Consul Ionin and slowly sailed along the coast amid rifle salutes and the incessant cries of ‘živio’ from the Montenegrins.”

— from Dr. A. V. Shcherbak, Montenegro and Its War with the Turks in 1877–1878 (1879)

As contemporary observers noted, “At last it happened! In 1878 Montenegro broke through to the sea.”

The Congress of Berlin

Yet this achievement immediately encountered resistance at the European level. The territorial gains confirmed by the San Stefano Preliminary Treaty (19 February 1878) provoked strong opposition in Vienna, Berlin, and London, where Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Great Britain viewed the strengthening of Russian and Montenegrin influence as unacceptable. Britain responded by sending a powerful naval squadron into the Sea of Marmara, threatening Russia’s Black Sea position, and prompting the convocation of the Congress of Berlin.

The Berlin Treaty sharply curtailed Montenegro’s maritime sovereignty. Montenegro was prohibited from possessing warships or a naval flag; the port of Bar and Montenegrin waters were closed to the warships of all nations; existing coastal fortifications were to be dismantled; and maritime and sanitary supervision of the coast was placed under Austro-Hungarian control. The revised treaty stated explicitly: “The port of Bar shall retain the character of a commercial port and may not be transformed into a military one.”

A gift from the Tsar Alexander

In 1890, by decision of Emperor Alexander III, Russia presented Montenegro with a modern civilian steamship, later known as Yaroslav. Although formally a merchant vessel, it could be quickly converted into an auxiliary cruiser. This ship became the first and only Montenegrin ocean-going steamship, crewed largely by experienced captains from Boka Kotorska, including Marko Berberović, who served as one of its first officers.

According to the account published by Lucija Đurašković in Primorske Novine, the Yaroslav was built in 1882 by the shipyard Denny and Bros., Dumbarton Ltd. The vessel was subsequently purchased by Russia as an insurance vessel and entered service in the Russian Navy as an auxiliary dispatch vessel , always carrying several cannons. For its time, Yaroslav was a large ship, with a cargo capacity of 2,600 tons and a speed of 15 knots. The vessel measured approximately 314 feet in length, 37 feet in width, with a draught of about 25 feet.

The engine room occupied about 66 cubic feet, and the ship was equipped with six steam boilers and two steam engines, each with 33 portholes on each side.

Blue Velvet, Monograms, and Imperial Portraits

According to a description published in the Constantinople newspaper Srpska nezavisnost, the level of comfort on board was exceptionally luxurious.

The saloon featured elegant and solid furnishings: two large sofas upholstered in blue velvet, a large armchair shaped like a small throne, and several wicker chairs arranged around a square table. Above the sofa hung a large mirror in a polished wooden frame.

Beneath the mirror, inside a cabinet, stood a large white porcelain washbasin. The saloon was further decorated with large portraits of the Montenegrin ruler and of the Russian imperial couple.

I wish the Tsar did not give us this ship

During the first years of her service, Yaroslav was quite active. She regularly sailed between Russia, Italy, and England, transporting cargo from Rijeka to France. However, it soon became evident to the experienced Bokelj captain Andrija Đurković (1850–1895) and his officers that this ship was, in his own words, the fruit of a poisonous tree.

Lucija Đurašković, writing in Primorske novine, reports the following words from the captain’s diary:

“Only one thing troubles me, as if I myself were to blame—and that is that His Imperial Highness Alexander III decided to present a steamship to His Highness Prince Nikola I, but did not give him a ship that would serve him well, but rather one that would cause him damage.”

The reasons were concrete and measurable. How could a steamship be profitable when it required a crew of at least 45 men, whereas a vessel of comparable tonnage would normally require no more than 28? Yaroslav consumed 24 tons of coal per day, while other modern steamships of the time burned about 8 tons per day, making her operation economically unsustainable from the outset.

The last voyage and the death of Captain Andrija

The last voyage of the Yaroslav concluded only a few days before the death of Tsar Alexander III on 1 November 1894. The ship was first anchored off Perast and, in the spring of the following year, transferred to Risan. As often happened, the fate of the vessel closely followed that of her captain: on 11 April 1895, Captain Andrija Đurković died suddenly at the age of 45.

With a new emperor on the Russian throne and the death of Captain Đurković, the Prince of Montenegro no longer needed to maintain the fiction of appreciation for the gift. In 1895, the ship was disarmed and sold back to Russia. Upon her return, she was entered into the Baltic Fleet under her original name, Europa (Европа).

A new life for the Yaroslav, ending in Helsinki

From 1900, Europa served as a training vessel, and from 1909 as a transport ship. In the autumn of 1910, she was converted into a submarine base. From 28 December 1916, she served as Blockship No. 10 (Блокшив №10) and, following the Revolution, passed under the Soviet flag. In April 1918, the vessel was left in Helsingfors (Helsinki); on 4 June 1918, she sank due to water ingress into the hull. The ship was later raised and scrapped for metal.

The Order of Danilo I

For their service aboard the Yaroslav, Captain Andrija Đurković and First Officer Marko Berberović were awarded the Order of Danilo I by Prince Nikola of Montenegro. Following the decommissioning of the Yaroslav, the thirty-two-year-old Marko Berberović remained in the service of the Montenegrin Crown.

Source: Dim Dimych, article published in 2016, link. Lucija Đurašković, Primorske Novine, “Yaroslav” — the first Montenegrin ocean-going steamship, publsihed in two parts: 31 March 2003 and 30 April 2003. Srpska nezavisnost, “Srpski parobrod na zlatnoj ruti”, VII/51 (Belgrade, 2 May 1891) as cited in Lucija Đurašković in Primorske Novine (2003). Fleetphoto, Russian Vessel Database, Blockship No. 10 (State of California, Europa, Yaroslav), entry 71343 — link .

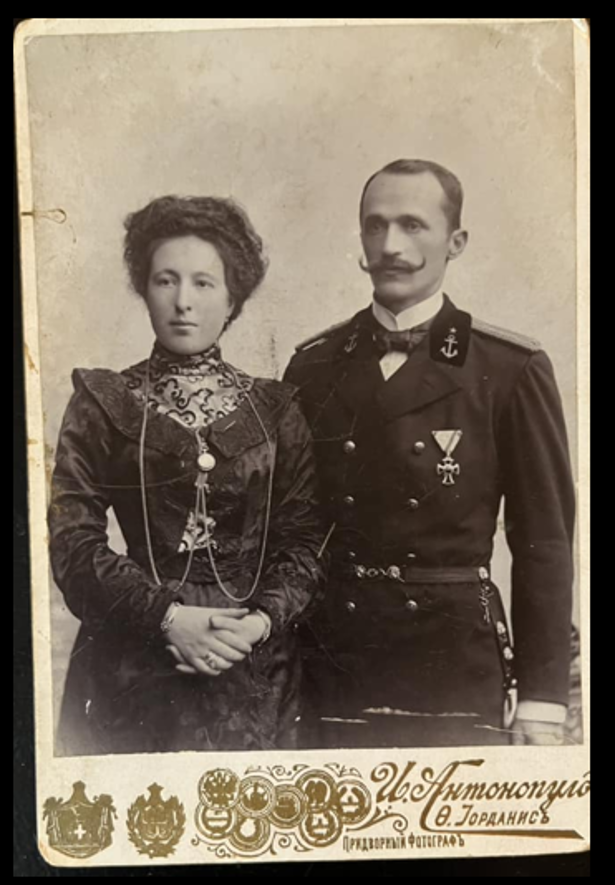

Marko and his wife Ana Dabović in Odessa (c.1903)

Captain Marko Berberović and his wife Ana Dabović, Odessa.

This studio portrait was taken in Odessa by the photographic atelier of Ivan Antonopulo.

Based on Marko Berberović’s rank insignia and the presence of a single decoration — the

Order of Danilo I, awarded by the Prince of Montenegro — the photograph can be dated to

the first years of the couple’s stay in Odessa, possibly as early as 1903, when Marko

and Ana had recently moved there.

Ana Dabović was a native of the Bay of Kotor and the elder sister of Captain Mirko Dabović, who would later become commander of the submarine fleet of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Mirko Dabović died in action on 14 October 1944, during a mission to exfiltrate a United States officer from occupied Yugoslavia to liberated southern Italy. He was killed under German fire in the Adriatic Sea, in front of the Mamula fortress, in the waters of his native bay.

Original photograph from the private collection of the Ćulafić family.

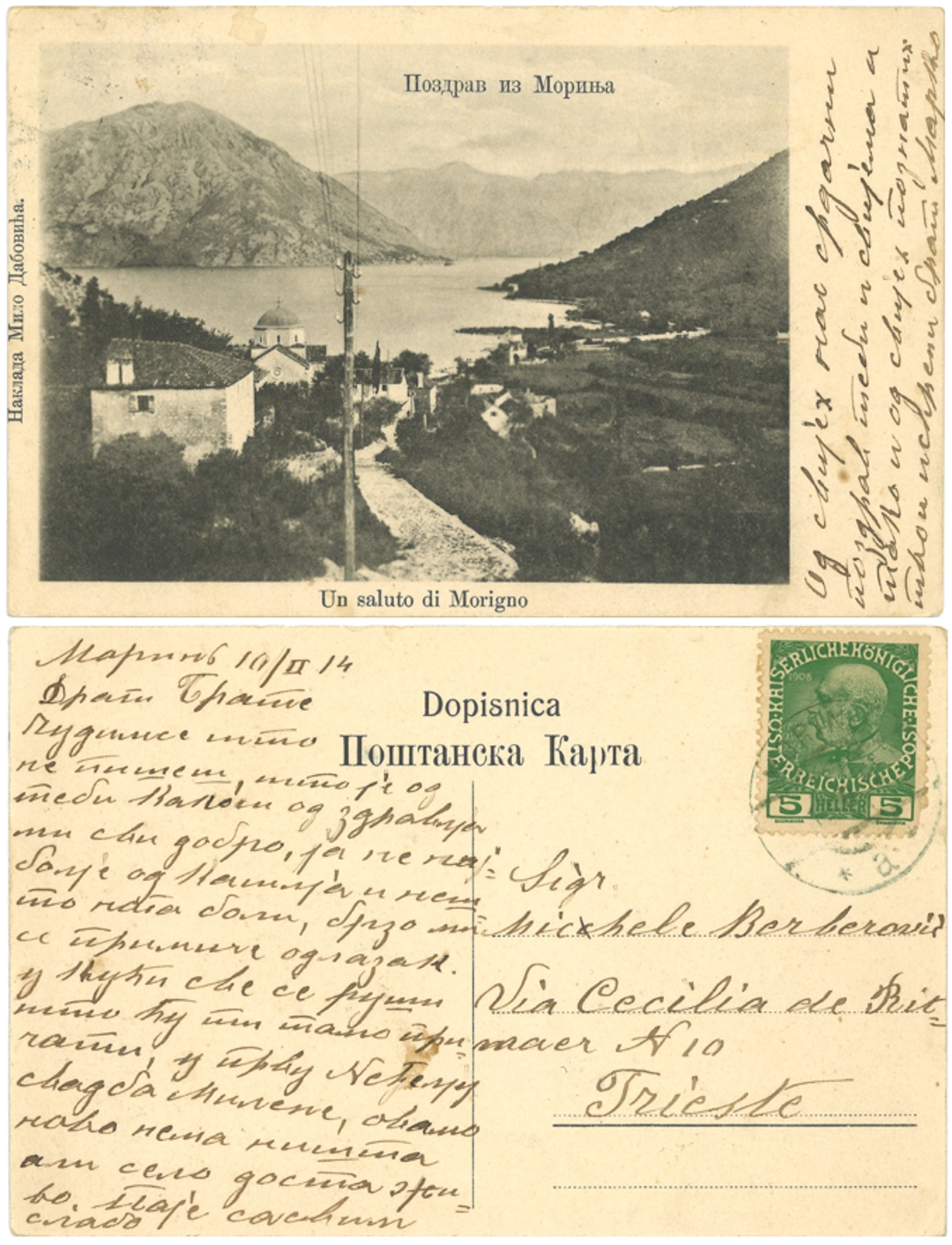

A last visit to Morinj (February 1914)

In February 1914, Captain Marko Berberović and his wife Ana Dabović spent some time in Morinj, likely for the last time before the outbreak of the First World War. From Morinj, Marko wrote to his brother Milivoj in Trieste on 10 February 1914. In the postcard, he explicitly expresses surprise at the lack of news from Trieste, suggesting that communication between the two brothers was already difficult at that time.

Continue reading →

Censorship and correspondence

It cannot be excluded that Marko’s correspondence was affected by wartime or pre-war censorship. By then, Marko was serving as a ship captain in the Russian merchant navy, based in Odessa, a position that may have attracted particular scrutiny in cross-border communications with Austro-Hungarian territory.

An Imperial Russian passport

In the family archives, there is a copy of a passport issued to Ana Berberović, née Dabović, by the Imperial Russian Consulate in Trieste, dated March 1914. This raises open questions: did Marko ask his brother Milivoj to arrange the passport on his behalf? And why was the document never delivered to Marko and Ana? The passport remained in Trieste and was never used.

Later that same year, the war broke out. Marko and Ana spent the war years in Crimea, while Milivoj remained in Trieste, where he died in November 1918. The two brothers never met again.

English translation of the postcard

Morinj, 10 February 1914

Dear brother,I am surprised that you do not write and that I hear nothing from you. How is your health? We are all well; I myself am not so well because of a cough, and my legs hurt a bit — my departure is approaching quickly.

At home they will understand what I will tell you there. On Sunday there will be Milena’s wedding at the church. Here there is nothing new, but the village is quite ill-humored; Paje is completely unwell…

A heartfelt greeting to you and your family from all of us, as well as from all [your] acquaintances.

Your sincere brother, Marko.

Captain at war (1914–1921)

And the years of the Russian Revolution in Odessa

As Russia entered the First World War, Captain Marko Berberović and his wife Ana Dabović found themselves effectively stranded in Odessa. Marko, who was then serving in the Russian Merchant Navy, was commissioned as a captain in the Imperial Russian Navy when the Volga (Волга), his cargo steamship, and her entire crew were mobilized and included in the Danube Special-Purpose Expedition.

The Ottoman attack on Odessa

It all started with the shelling of Odessa, which took place during the Black Sea Raid on 29 October 1914. On that day, Ottoman naval forces attacked several Russian Black Sea ports, including Odessa, Sevastopol, Novorossiysk, and Feodosia, shortly before Russia and the Ottoman Empire formally entered the war against each other in World War I.

Once again in history (and for the very last time), a Captain Berberović found himself under the fire of Ottoman cannonballs. Did Marko, standing on the deck of his ship, remember the stories of the brothers Andrija and Krsto Berberović? Did he think of his own grandfather, Captain Marko Petrov, facing corsairs and their attacks?

And there he was, in a foreign harbour, with more than two centuries of maritime tradition in his name, standing in front of the enemy. This time, however, his ship was not equipped with cannons and lead balls. No newspaper reported how Captain Marko managed to save his vessel and the lives of those on board.

In their apartment on Польская д. 3 Квар. № 16 (Pol'skaya, House No. 3, Apartment No. 16) a central street of Odessa, his wife, Ana Dabović, waited for his return while fire and smoke covered the harbour and the sea.

Continue reading →

From the Tsar to the Revolution of 1917

Following the Ottoman attack, the Tsar ordered the requisition of all commercial vessels into the Imperial Russian Navy. At the beginning of 1915, Marko, a subject of the Austrian crown who had sworn allegiance to the Montenegrin Prince, was confirmed in command of the Volga, now commissioned as a military naval vessel, wearing the ranks and insignia of the Tsar.

From 10 February 1917, the steamship was entered into the 3rd Division of the Minesweeping Brigade of the Black Sea Fleet as minesweeper T-231, and from October of the same year as T-331.

In March 1917, following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the February Revolution, authority in Odessa passed to the Provisional Government. Marko and the Volga continued to serve under the former Imperial command structures during this transitional period.

After the October Revolution (7 November 1917), power in Odessa changed hands repeatedly. In June 1917, the minesweeper was temporarily assigned to the Transport Flotilla, and from May 1918, following the establishment of Ukrainian authority in the city, it became the minesweeper Volga of the Ukrainian Fleet.

From February 1919, after Odessa was taken by anti-Bolshevik forces, the vessel served within the Naval Forces of South Russia (the White movement) as the minesweeper-base Volga. In early 1920, it was reorganized as a transport ship. On 3 September 1920, Volga struck a mine in the Sea of Azov, but remained afloat and was towed to Sevastopol for repairs.

Captured by the Red Army

By the time of General Wrangel’s evacuation of Crimea in November 1920, the repairs had not been completed, and on 15 November 1920 the transport Volga was captured in Sevastopol by Red Army forces. From that moment, Marko’s service came under Bolshevik (Red) control.

After the completion of repairs, the vessel was entered into the Naval Forces of the Black and Azov Seas as a minesweeper, receiving the designation T-16 in March 1921. From 20 June 1921, the ship was again listed as the transport Volga, and from July as a port vessel.

A captain of many flags, and one sea

Born in 1862, Marko Berberović was a subject of the Austrian Empire at birth (the Austro-Hungarian Compromise would follow in 1867). He received his maritime education and graduated as a captain in Trieste, the main port of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Between 1914 and 1921, through successive changes of power in Odessa, Marko Berberović served first the Imperial Russian Navy (Tsarist authority), then the Ukrainian Fleet, followed by the White forces of South Russia, and finally under Soviet authority within the Naval Forces of the Black and Azov Seas. Across these years of war, revolution, and civil conflict, Marko Berberović’s allegiance was to the sea.

Sources: Bureau Veritas, Repertoire Général – General List of Merchant Shipping of All Nations: Steamers and Motor Vessels, 1914–1915, Paris, 1915 — link . Kruiznik, entry on Товарный пароход «Волга» by Vitalis Merta (2011) — link Militera, Russian military history library, Combat composition of the fleets of the opposing sides in the Black and Azov Seas, 1920 (Боевой состав флотов противоборствующих сторон на Черном и Азовском морях, 1920 год), link.

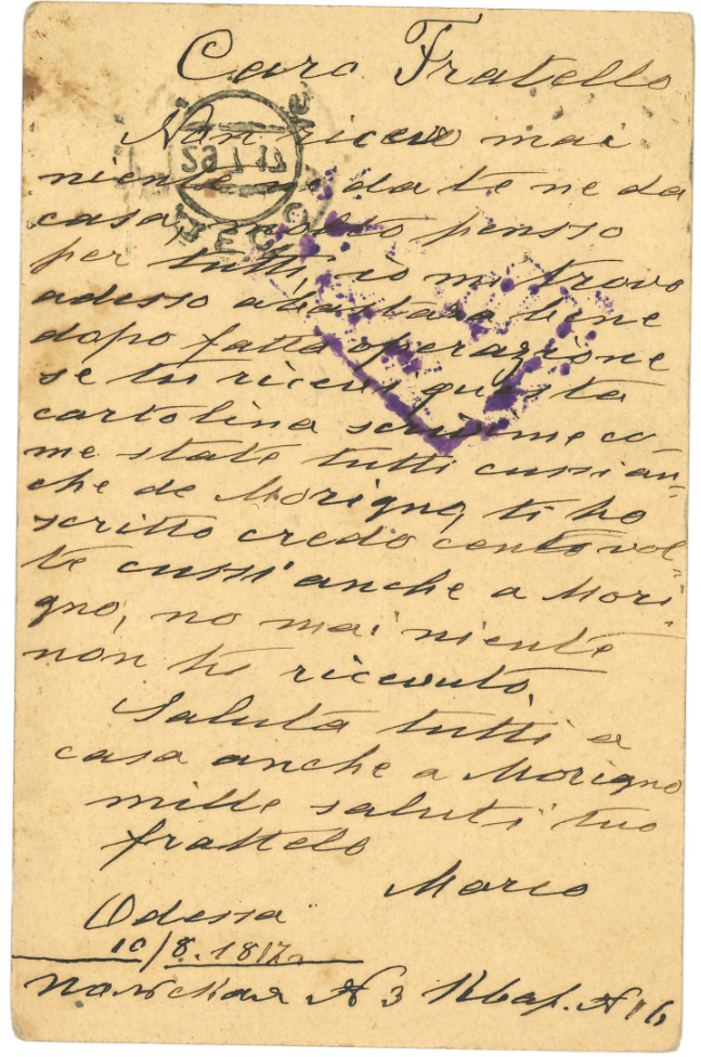

A postcard from Odessa, Summer 1917

An exceptional document with sentimental and historical value

One of the most surprising documents in the family archives regarding Marko Berberović's life in Odessa is a postcard sent from Marko to his brother Michele (Milivoj) in Trieste. The postal stamp on the card is marked Одесса (Odessa) and dated 29 July 1917. In this message, Marko complains to his brother about the lack of news from him and the family in Morigno, noting that he has written "perhaps a hundred times" without receiving a single reply. None of those many letters survive; most likely, they never reached their intended destination. We do not know if Milivoj attempted to contact his brother, but if he did, those letters never arrived in Odessa.

Continue reading →

Crossing the front line in times of war and revolutions

To understand the exceptional nature of this correspondence, one must look at the context of 1917. Trieste, where Milivoj resided, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as was the family's home in Morinj (Morigno). Meanwhile, Marko had been commissioned in the Imperial Russian Navy as the commander of the Volga, a cargo ship converted into a minesweeper. Because the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires were at war, any correspondence between Odessa and Trieste was nearly impossible, passing through enemy lines and the Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, as an Austrian-born subject commanding a Russian Imperial ship, Marko’s communications were undoubtedly subject to heavy censorship.

In Odessa, the period between the February Revolution and the October Revolution was one of profound instability. By the summer of 1917, the city was in a state of "dual power" and social ferment. Following the Tsar's abdication, authority was split between the Provisional Government and the local Soviets. The streets were a mosaic of political rallies, rising bread prices, and a breakdown in traditional municipal order. While the city remained a cosmopolitan hub, the euphoria of the early revolution had given way to anxiety over the failing Kerensky Offensive and the looming threat of Bolshevik radicalization.

The situation in Trieste and Morinj

The situation in Trieste during the summer of 1917 was equally dire. As a primary port for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the city suffered under a British naval blockade that led to severe food shortages and "hunger riots." Similarly, in Boka Kotorska, the local population faced extreme militarization and scarcity. The bay had become a heavily fortified naval base for the Austro-Hungarian fleet, and the civilian population—including the Berberović family in Morinj—lived under the constant shadow of the war and the watchful eye of imperial authorities.

Marko's desperate plea for news reflects the crushing isolation and uncertainty of the era. He and his wife, Ana, had last visited Trieste and Morinj in 1914, returning to Odessa just as the war erupted. In the postcard, Marko also mentions a recent "operation," though he provides no further details. It remains a mystery whether this was a medical procedure resulting from an injury sustained during his service on the Volga or a non-combat illness.

An exceptional document

The sentimental value of this document mirrors its immense historical weight. For two centuries, generations of Berberović and Bokeljan captains had navigated the route between Odessa and Trieste, braving Greek and Turkish pirates. Nothing had stopped the likes of Andrija or Krsto from crossing those waters. But as the world was torn apart by total war and revolution, the times inexorably changed. There was nothing our last Captain Berberović could do to reach his brother, save for this single, fragile postcard that somehow defied the censors and the front lines.

Original Italian:

Caro Fratello,

Non ricevo mai niente ne da te ne da casa, molto penso per tutti, io mi trovo adesso abbastanza bene dopo fatta operazione se tu ricevi questa cartolina scrivimi come state tutti cussì (?) anche de Morigno ti ho scritto credo cento volte cussì (?) anche a Morigno, no mai niente non ho ricevuto.

Saluta tutti a casa anche a Morigno mille saluti tuo fratello

Marco.

English Translation:

Dear Brother,

I never receive anything, neither from you nor from home. I think of everyone a lot. I am doing well enough now after having had an operation. If you receive this postcard, write to me [to tell me] how everyone is also [regarding] Morigno. I have written TO Morigno I think a hundred times; [I wrote] to [unreadable] Moriano too, but no, never anything, I have received nothing. Greet everyone at home and also in Morigno.

A thousand greetings, your brother,

Marco.

Note: The date on the official postal stamp indicates 29 July 1917, whereas Marko's autographed text is handwritten as "10 August 1817". There is no definitive explanation for the use of "1817"; perhaps it was a code word between the two brothers, a way to communicate something specific while skipping censorship. In this context, it is also interesting to observe that Marko chose to write in Italian (most likely unreadable by the Russians) instead of Serbian.

Marko Berberović in Morinj, Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1930s)

A photo take in Morinj on 22 June 1926. The same photo was later published in Belgrade’s Illustrated Newspaper (Ilustrovani list), no. 35, dated 29 August 1926, accompanying an article on the consecration of the bells for the Cathedral Church of St. Sava in Morinj.

According to Momir Milinović, who provided this photograph, the central figure is the young priest Mihailo Barbić (later killed by the Communists). Beside the man who is wearing a white uniform and carrying a sabre is Bogdan Ljubov Milinović, then knez of Morinj. Captain Marko Berberović appears in the second row, positioned between the man in the white uniform and an older Orthodox priest.

Standing behind Captain Marko is Đuro Vasov Milinović, identifiable by his distinctive hairstyle. In the front row, wearing a dark jacket and white trousers, is Dr. Uroš Seferović, later president of the Serbian National Defense in America. On the far left, next to Bogdan Milinović, with a flower in his lapel and a thick grey moustache, is the Morinj merchant Nikola Markov Seferović.

Captain Marko Berberović and his wife Ana Dabović with Ana’s niece Zdenka on her wedding day, Morinj, September 1938. Photograph from the private collection of the Ćulafić family.

© 2025 - 2026 Riccardo Bevilacqua. All original text, structure, and commentary on this page are the intellectual property of the author, unless otherwise stated. Historical sources, quotations, images, and documents explicitly cited are used according to their original publication status and may be in the public domain or subject to their respective copyrights.