The Berberović family of Morinj

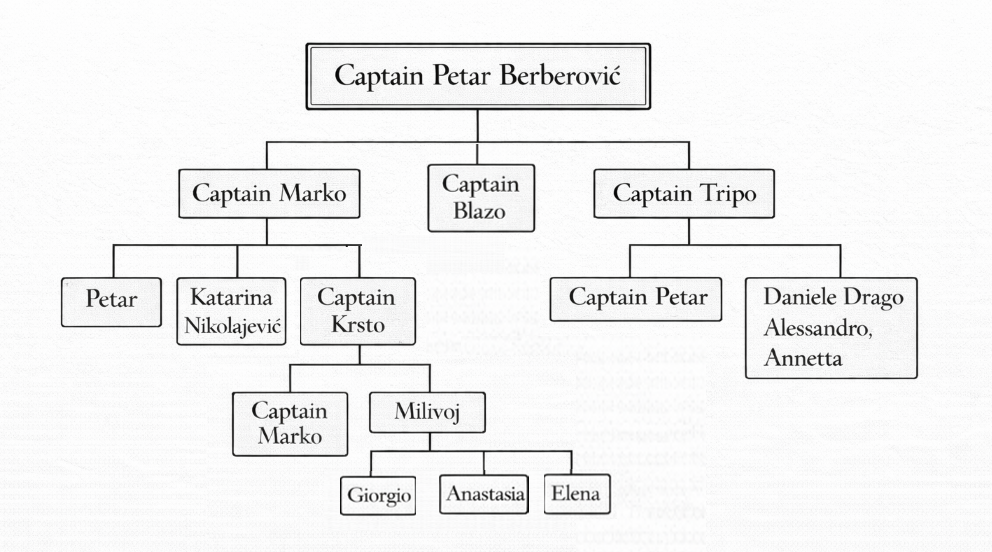

Berberović family genealogy: captains and priests of the Bay of Kotor (Boka Kotorska)

This page collects modular notes on key members of the family (Italian: Berberovich, Serbian: Берберовић) and on significant historical episodes. Each card is intended to stand on its own, can be expanded over time, and includes bibliographic references.

Legend: ★ = direct ancestor

Quick navigation

The settlers of Morinj (1687)

From Popovo Polje to the Bay of Kotor: defending the Venetian–Ottoman frontier

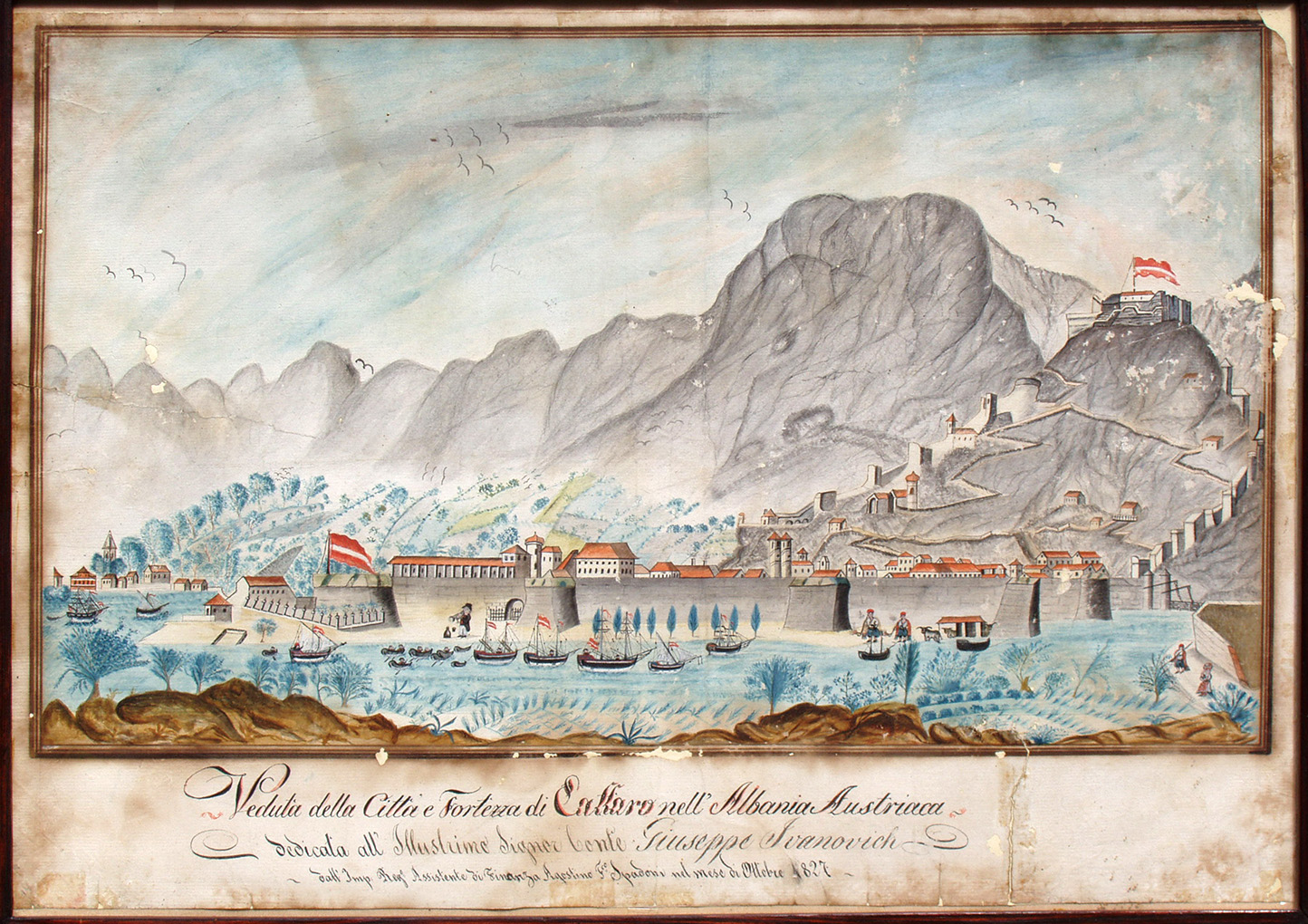

To learn how the first members of the Berberović family decided to settle in the Bay of Kotor (Boka Kotorska), we need to take a step back in time. The Bay had a unique and strategic role in controlling the commercial routes across the Adriatic Sea, and it was fragmented between cities under Venetian rule and others under Ottoman rule. This fragile equilibrium exploded following the Siege of Vienna in 1683, when the Christian powers of Europe launched a coordinated counter-offensive against the Ottoman Empire. In the Adriatic theatre, it was natural for the Republic of Venice to assume a leading role, initiating the Morean War (1684–1699), in order to consolidate its control over strategic positions along the Adriatic frontier.

In this context, the men of the Berberović family, a priestly Serbian Orthodox Christian lineage living under Ottoman rule, decided to fight for the Holy League, by enlisting in the Venetian navy.

Continue reading →

Conquering the Bay of Kotor

Before the Morean War, the Republic of Venice governed only Kotor (since 1430) and Perast. However, access to the Bay was controlled by the Ottomans, who held Herceg Novi (Castelnuovo), a strategic maritime stronghold. Life on the land frontier was no more peaceful than at sea. In his book History of the European wars following the appearance of Ottoman arms in Hungary in 1683, the Venetian nobleman and historian Nicolò Beregani explicitly mentions the village of Morinj (Morigno) in the Bay of Kotor among the settlements affected by Ottoman raids and devastation against Christian populations.

During the Morean War, Venice expanded and consolidated its control in the Bay of Kotor by capturing Herceg Novi in 1687, gaining control over access to inner Boka. One year later also Risan fell under Christian control. And by the end of the War, Venice controlled almost the entire Bay of Kotor, turning it into a fortified Adriatic frontier against the Ottoman hinterland.

A 250 years long deed

It was within this broader framework that, according to historian Špiro Milinović, the Berberović family settled in Morinj in 1687, along with other families that had distinguished themselves through military service in support of the Venetian Republic. As with other loyal frontier families, land was not granted merely as compensation for service, but above all as part of Venice’s policy of stabilising the frontier through permanent Christian settlement. These families had proven loyal to the Republic and were expected to fight to defend the frontier.

As the following pages will show, for over 250 years the Berberović kept the deed — until the dissolution of the empires at the end of World War I changed the world forever.

Archival evidence

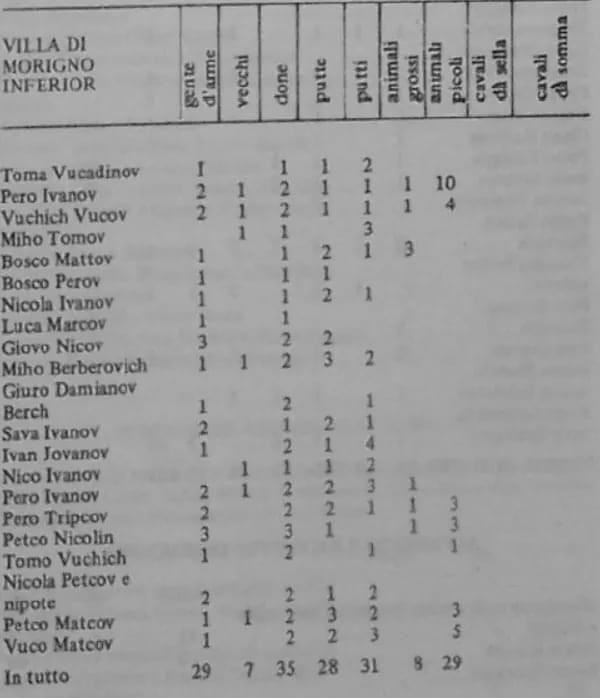

The early establishment of the family in Morinj is confirmed by the Venetian census of 1704, which records the Berberović among the inhabitants of the “Villa di Morigno Inferior” (Donji Morinj / Доњи Морињ).

1704 Venetian cadastral survey (pericazione) published in Spomenik

In Spomenik Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti, vol. 125 (1983) — a long-running scholarly series published by the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) devoted to the publication and critical editing of historical sources — several Venetian cadastral and fiscal documents are transcribed and published. is reporting the original information from the 1704 Venetian cadastral survey “pericazione” , documented in the “1704 Venetian cadastral records for Herceg Novi and Risano,”

In fact, catasti, estimi, and decime compiled after 1687, the year in which Boka Kotorska came under Venetian rule following the withdrawal of Ottoman authority.

Pericazione header (original language) and English translation

LAUS DEO 1704 CASTEL NOVO

Pericazione delle terre del territorio di Risano principiata sotto il regimento dell’Eccellentissimo Bartolo Moro, proseguita poi nella maggior parte e terminata interamente da me Pietro Rossi publico perito per ordine dell’Illustrissimo et Eccellentissimo signor Fenzo Badoer, proveditor extraordinario attual di Cattaro et Albania con la sopraintendenza di Castel Novo, esecutivo alle commissione supreme dell’Eccellentissimo Senato et dell’Eccellentissimo signor proveditor generale, fatta à villa per villa con l’intervento delli vecchiardi e villici che erano comunemente nominati

English translation

In the name of God, 1704, Castel Novo. Land survey (pericazione) of the territory of Risano, begun under the administration of the Most Excellent Bartolo Moro, later continued for the most part and completed entirely by me, Pietro Rossi, public surveyor, by order of the Most Illustrious and Most Excellent Mr. Fenzo Badoer, extraordinary provveditore currently of Cattaro and Albania, with the supervision of Castel Novo, executing the supreme commissions of the Most Excellent Senate and of the Most Excellent general provveditore, carried out village by village with the participation of the elders and villagers who were commonly appointed.

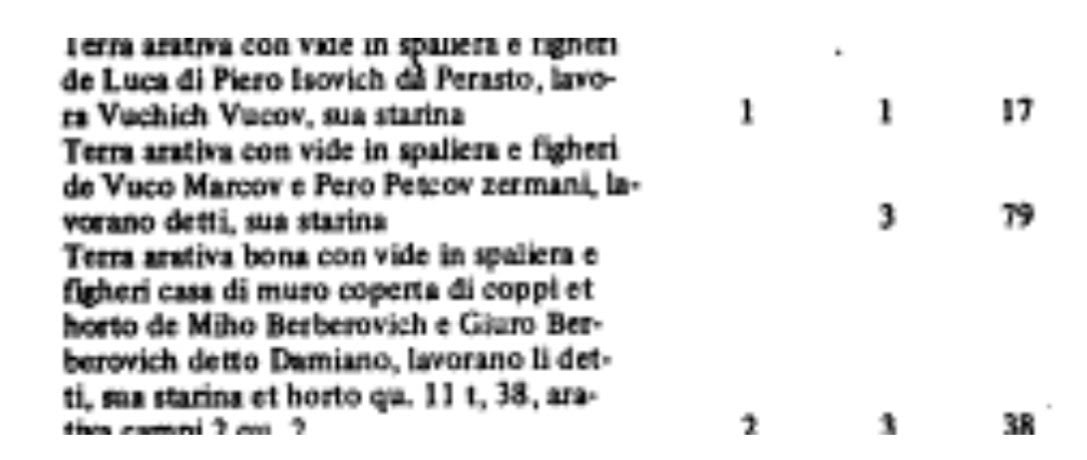

Miho and Giuro (Đuro) Berberović in the 1704 records

In these records, two individuals are listed as Miho and Giuro (Đuro) Berberović. In one instance, one of them is described as “called also Damiano”, while in another entry they are recorded jointly as “detti Damianovich”. This dual naming practice is typical of Venetian administrative documents, which often preserved patronymics, branch names, or transitional surnames alongside an emerging family name. Taken together, these references most plausibly suggest that Miho and Giuro were second-generation Berberović, likely the two sons living in 1704 of an earlier Damian (Damiano) Berberović, who appears to have settled in Morinj shortly after 1687, when Venetian authority was established.

Transcription from the 1704 census

Terra arativa bona con vide in qualita e figheri casa di muro coperta di coppi et horto de Miho Berberovich e Giuro Berberovich detto Damiano, lavorano li detti, una ratania et horto q. 11 l. 38, arativo …

Miho e Giuro Berberovich detti Damianovich

English translation

Good arable land with vines of good quality and fig trees, a stone house roofed with tiles and a garden belonging to Miho Berberović and Giuro Berberović, called also Damiano. The said persons cultivate one vineyard plot and a garden, measuring [units] 11, 38, arable land …

Miho and Giuro Berberović, known as Damianović.

Sources note: Spomenik Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti, vol. 125 (1983), Српска академија наука и умјетности, 1983.

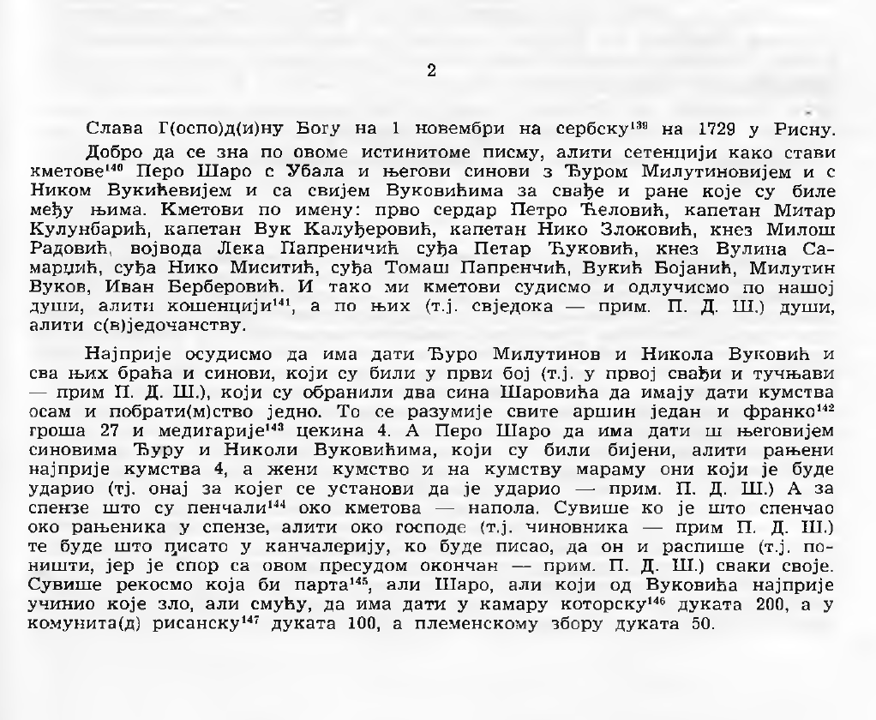

Court of the good men (Sud dobrih ljudi), Risan 1729

Ivan Berberović is mentioned in a court document from 1729, where he took part as a judge (kmet) in a judgment in Risan concerning a settlement between Pero Šaro, together with his sons and his sons’ sons, and Đuro Milutinović and Nikola Vuković, along with the entire Vuković family, "regarding the quarrels and wounds that had occurred between them" (Petar Šerović, 1961)

The kmetovi included, in addition to Ivan Berberović, Captain Niko Zloković, Knez Miloš Radović, and Vojvoda Leka Paprenčić. The ruling of the court of the good men of Risan concluded by decreeing that:

“Whoever commits wrongdoing or deception shall pay 200 ducats to the Kotor chamber, 100 ducats to the Risan community, and 50 ducats to the tribal assembly.”

The shipowner and the priest

Špiro Milinović, one of the most important historians covering the history of Morinj, notes that the maritime activities of these new inhabitants started to be documented within a generation from the first Serbian settlers. As far as our story is concerned, the first Berberović to be mentioned in a document related to the maritime trade was Andrija Berberović, a "shipowner from Morinj", who in 1756 was active in the maritime trade of wine.

A later document, also reported by Milinović, provides the first explicit reference to a clerical member of the family in Morinj. In an act dated 5 April 1775, preserved by Captain Vlado Ivelić of Risan, the princes and elders of Morinj acknowledge receipt of a princely order and sign on behalf of their respective brotherhoods. The document concludes with the statement that Priest Todor Berberović wrote the letter and signed it on behalf of the Berberović family, confirming their recognised religious and representative role within the community.

Sources: Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta (1974), reporting archival material from the family of Pop Nikola Berberović; Republic of Venice census, 1704; Šerović, Petar D. Prilozi za proučavanje narodnog života u Boki Kotorskoj u XVIII vijeku. In: Arhivska građa, Glasnik Etnografskog muzeja u Beogradu, Book 24, pp. 107–126.Belgrade: Ethnographic Museum, 1961; Nicolò Beregani, Historia delle guerre d’Europa dalla comparsa dell’armi ottomane nell’Hungheria l’anno 1683 (Venice, 1698).

Taking to the sea: the first Serbian captains (1700-1800)

Merchant ships and French cannons

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Serbian settlers of Morinj turned to seafaring. Alongside the wine trader Andrija Berberović, there were other families whom we will encounter later in this story. Špiro Milinović, in his detailed accounts of the historical records, mentions the brothers Đorđe and Nikola Dabović, shipowners from Kostanjica (note this name: two centuries later, the last Captain Berberović would marry the sister of Captain Mirko Dabović, commander of the submarine fleet of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and a war hero). Milinović also records the Kosić family, shipowners from Morinj, who obtained a sailing permit in 1729, as well as members of the Vulović brotherhood.

Continue reading →

Merchant shipping soon began to bring wealth to these families. This is confirmed by a document from the same period, also reported by Milinović, which records how Adam Berberović of Morinj purchased a field from Ivan Čuče of Perast for 150 thalers, “paid in coins”.

In January 1790, by order of the Venetian government, all sea captains in the Bay of Kotor were registered. By the early 1800s, there were more than a dozen captains belonging to the Berberović brotherhood active in the Bay. When, in 1807, the French military commander in Dubrovnik requested a list of armed vessels for each city in the Bay, historian Špiro Milinović reports that five captains from Morinj were included. Among them were Captain Špiro Berberović, commanding a brigantine armed with six cannons and crewed by twelve men, and Captain Luka Berberović, who commanded a smaller polacca equipped with four cannons and manned by ten crew members (Milinović, 1974).

According to Milinović, more than 100 seafarers aged between 18 and 42 were registered in the official list dated 5 October 1811. Several belonged to the Berberović brotherhood: Tripo; Đorđe; Ignjo; Nikola; Simo; Ilija; Andrija; Risto; Ignjatije; Tomo; Špiro Božidar; and Ivan. It is interesting to note that personal names often appear with different spellings, and that “misspellings” were very common in these registers. For example, “Risto” could also appear as “Kristo” (that is, Krsto or Cristoforo in Italian). In fact, both Serbian and Italian were used, written in different alphabets.

Sources: Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta (1974).

Captain Petar Berberović ★

A long-distance captain, and head of the house.

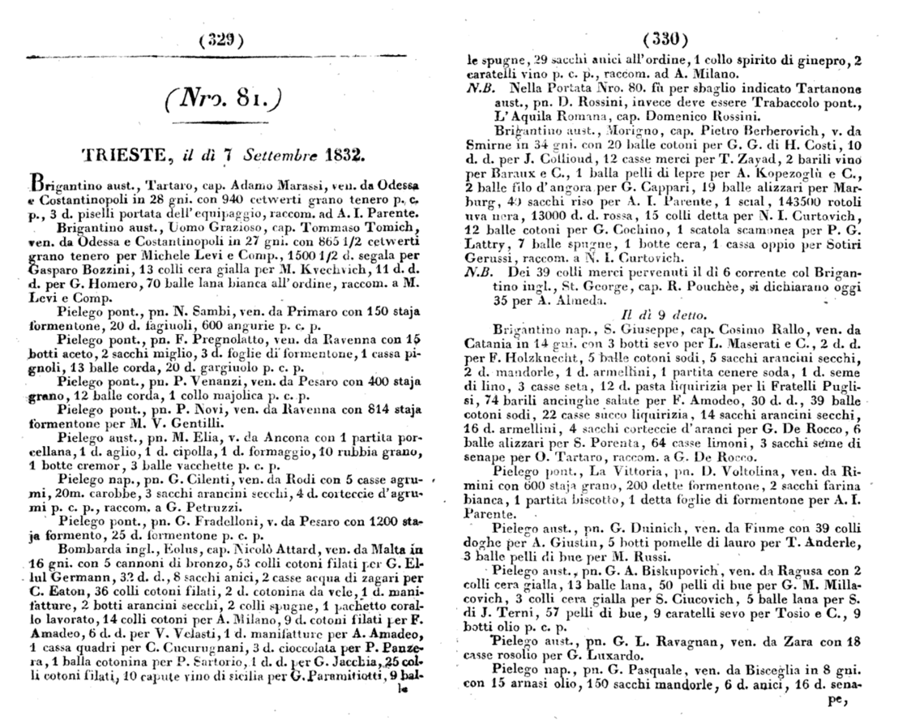

At the command of the brigantine Morigno, under Austrian flag, Captain Petar Berberović was sailing the Adriatic and Aegean commercial route connecting the port of Trieste with the coasts of the Ottoman Empire. And it is in fact in the port registers of Trieste that we can read most of what we know about Captain Petar's journeys. The year 1832 is particularly interesting as Petar was in his early 60s, and yet, still very active.

Continue reading →

- On 11 January 1832, Captain Petar (Pietro, as recorded in the Trieste registers compiled in Italian) arrived in Trieste after a 47-day voyage from the harbours of Smirne, Urla, and Sira. The cargo included 524 barrels of red grapes for the merchant Quequich, who commissioned the transport. In addition, the Morigno carried 19 smaller consignments for other merchants.

-

On 7 September 1832, Petar again arrived in Trieste with his brig Morigno,

this time after 34 days of sailing from Smirne.

The cargo included wine, hare skins, rice, wax, and opium.

The complete cargo list, with the names of the consignees, is reported in the Trieste registers as follows:

20 balle cotoni per G. G. di H. Costi, 10 d.d. per J. Collioud, 12 casse merci per T. Zayad, 2 barili vino per Baraux e C., 1 balla pelli di lepre per A. Kopezoglu e C., 2 balle filo d’angora per G. Cappari, 19 balle alizzari per Marburg, 49 sacchi riso per A. L. Parente, 1 scial, 143500 rotoli uva nera, 13000 d.d. rossa, 15 colli detta per N. I. Curtovich, 12 balle cotoni per G. Cochino, 1 scatola scamonea per P. G. Lattry, 7 balle spugne, 1 botte cera, 1 cassa oppio per Sotiri Gerussi, raccom. a N. I. Curtovich.

- On Christmas Day, 25 December 1832, a third arrival of the Morigno in Trieste is recorded. The voyage from Smirne took only 28 days. The cargo included 527 barrels of red grapes for A. Gialussi, 208 quintali of boxwood (legno bosso) for J. Collioud, and 15 bags of anise for Anastasio Eulambio, among several smaller consignments.

A test of command: Captain Petar Berberović in the storm of 1832

The following episode is reported here as it is particularly revealing of Captain Petar Berberović’s character and judgement at sea. It is documented in contemporary records from 1832 and was first published in the Godišnjak in 1956. The same account was later reproduced by Špiro Milinović in his 1974 study of Morinj.

The brigantine “Morinj” was sailing with a cargo of dried grapes (raisins) from Smyrna to Trieste. On 1 January, it was forced, due to strong southerly winds, to anchor in the open sea in front of the main entrance to the port of Chioggia. For the entire day and night, the ship remained at anchor, battling heavy winds and waves, in constant danger of sinking with the entire crew.

In this situation, Captain Berberović, after consulting with the ship’s crew, decided to cut the anchor chains and attempt to enter the port or, if that should fail, to run the ship aground and thus save the crew. This difficult manoeuvre was carried out with great skill and courage. He succeeded in bringing the heavily damaged ship and its equipment safely into the port of Chioggia.

The Petar Berberović lineage

Maritime records allow us to trace the family lines of the captains from Morinj, as they often record patronymics, and the names of ships and routes were also linked to specific houses. Unfortunately, no patronymic is recorded for Captain Petar. Nevertheless, we can trace his children and the children of his children. Petar is also central to this story, as he is the oldest direct ancestor of the author along the Berberović line who can be confidently identified. If more information becomes available, this section will be updated.

Sources: Portata dei bastimenti arrivati nel porto-franco di Trieste l’anno 1832. Trieste: Tipografia Eredi Coletti, 1832. Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta. Godišnjak. Montenegro, n.p, 1956.

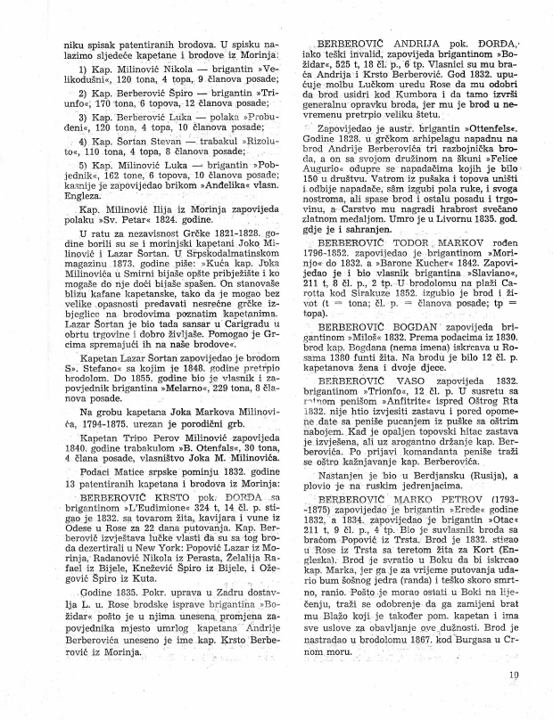

Captain Andrija Berberović, son of Đorđe (c.1790-1835)

One-armed captain, pirate cannonballs, and death from cholera

Andrija Berberović (Andrea Berberovich in Italian) was born in Morinj more than 30 years after the wine trade of his homonymous Andrija was recorded in the Venetian registers (please do not get confused: names were repeated from one generation to the next, so the patronymic was as important as the given name in distinguishing individuals).

The son of Captain Đorđe Berberović and Anna Panjotti, Andrija qualified in Trieste, where he passed the examination for Captain of Long-Distance Navigation. I wonder whether he could ever have imagined, on the day of his graduation, how years later a pirate cannonball would change his life forever.

Continue reading →

Serving in the Austrian navy

Recruited by the Austrian navy, Captain Andrija rose fast and, before turning thirty, commanded the brigantine Ottenfels. As described by Vasko Kostić in Exploits of the Boka Sailors Beyond Boka (Подвизи Бокеља ван Боке), those years gave him combat experience, skill, and the confidence to take his own ship.

Those were turbolent years: in June 1814, the Great Powers decided that the Bay of Kotor (Boka Kotorska) would be returned to Austria, ending the short-lived union with Montenegro. In Odessa, the secret movement Filiki Eteria was founded, and on 25 March 1821 the general uprising in Greece was proclaimed, triggering (yet another) war across the Peloponnese.

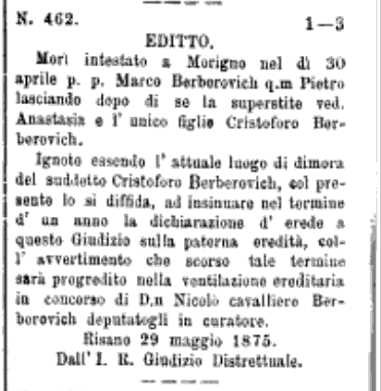

Ottoman blockades and first encounters with the pirates

With the outbreak of the Greek uprising in 1821, Andrija left the navy and took command of his schooner Felice Auguri. The eastern Mediterranean was flooded with pirates, many operating from Gramvousa, the rocky stronghold near Crete. Felice Auguri was small but armed: 15 men, 10 cannons, half the crew always off duty. According to Kostić, Andrija was also known for his bravery, and he was one of the few captains daring to slip supplies through Ottoman blockades—and at night, keeping the watch himself while sailing those dangerous waters.

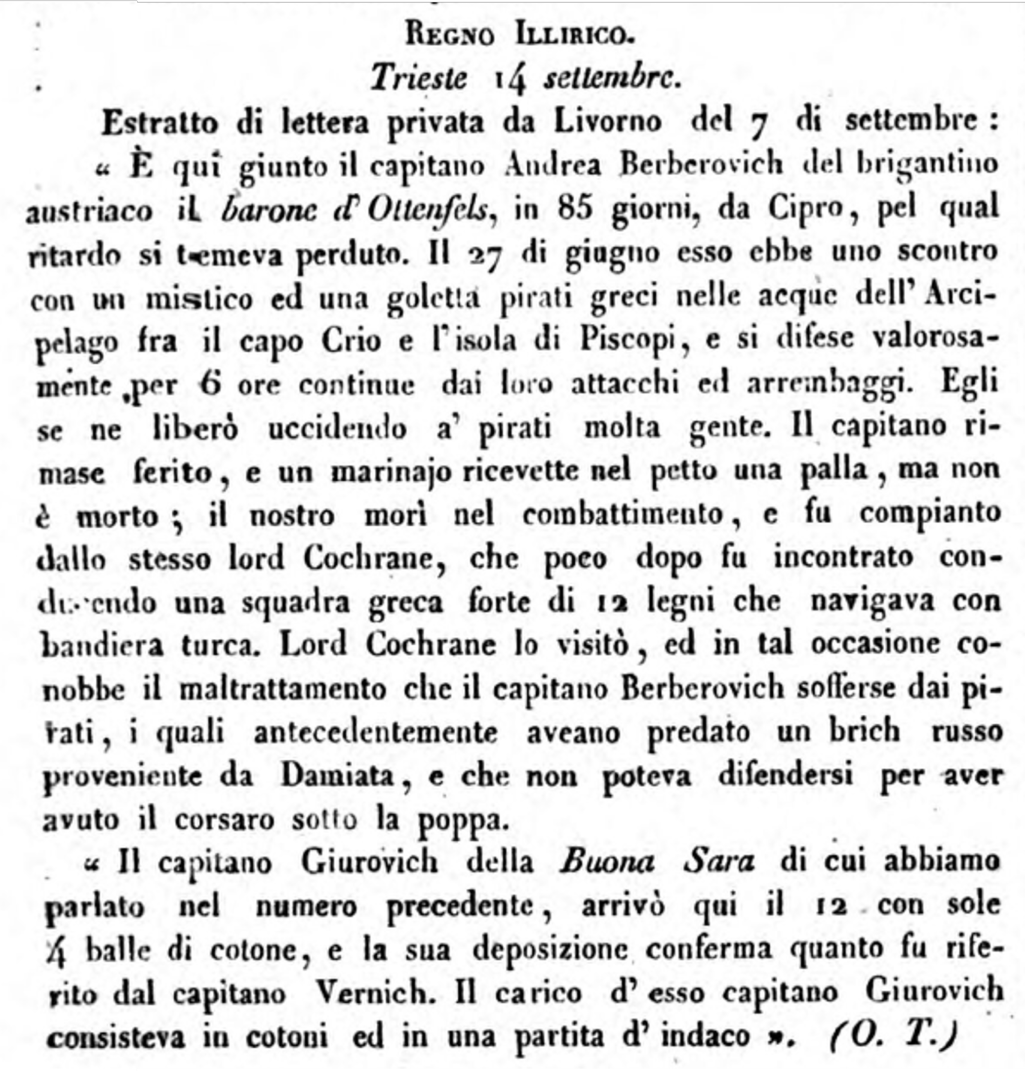

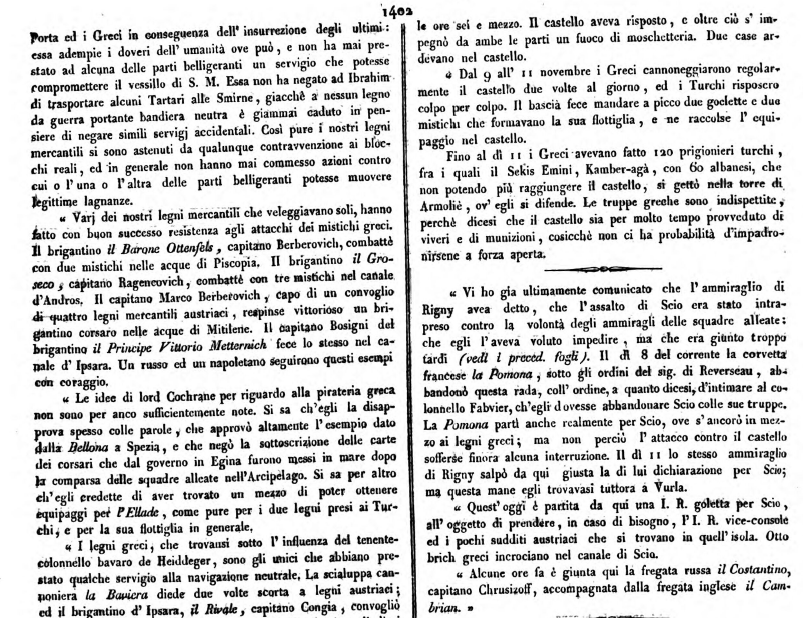

Extract from a letter from Livorno dated 7 September 1827 published by the Gazzetta di Milano.

Captain Andrea Berberovich of the Austrian brigantine Barone d’Ottfels arrived here, after 85 days, from Cyprus, where he was feared lost due to the delay. On 27 June he had an encounter with a mystic and a Greek pirate gunboat in the waters of the Archipelago, between Cape Crio and the island of Piscopi, and defended himself bravely for six consecutive hours against their attacks and boarding attempts.

He managed to free himself by killing the pirates’ leader. The captain was wounded, and a sailor received a bullet in the chest, but did not die; our men were victorious in the engagement and were accompanied by the same Lord Cochrane, who shortly thereafter encountered a Greek squadron of ten vessels sailing under the Turkish flag. Lord Cochrane visited him, and on that occasion learned of the mistreatment that Captain Berberovich had suffered at the hands of the pirates, who had previously captured a Russian brig coming from Dania, which he could not defend because the corsair had positioned itself under the stern.

A change in fortune and a fateful cannonball

Fortune turned in 1829, in the final phase of the war: one night, sailing beyond enemy lines, three larger ships closed in under a calm, moonlit sky. Andrija understood that escape was not possible, so he decided to slow down the Felice Auguri. Two pirate ships moved to board, one on each side, while a third covered them with cannons. At musket range, Andrija ordered his crew to attack: five cannons to one side, five to the other. Both pirate ships caught fire almost immediately.

Only then did Andrija order the sails raised and try to escape. However, the third enemy ship fired its cannons while recovering survivors. One cannonball struck the command bridge: the helm shattered, the boatswain was killed, and Captain Andrija’s left arm was smashed below the elbow. With no surgeon on board—and the only man trained in first aid dead—Andrija cut off his own arm with a sabre, told a crewman how to bind the wound, and stayed conscious long enough to bring ship, cargo, and crew safely to port.

The story travelled fast—from the Aegean to the Bay of Kotor, from the Bay to the Imperial court in Vienna. Once verified, the Emperor awarded Captain Andrija Berberović the Gold Medal for Bravery.

The last journeys and a sad day in Livorno

As soon as he could stand, Andrija went back to sea. He took command of the brigantine Božidar, owned jointly with his brother Krsto (18 men, 6 cannons). His name appeared again in the newspapers when, about four years after the Aegean battle, Andrija was caught in a violent Adriatic storm and managed, against all odds, to bring the damaged ship into Kumbor for repairs.

In 1835, during cargo operations in Livorno, his health—undermined by the wounds received in his battle with Greek pirates in Ottoman waters—suddenly worsened. Captain Andrija Berberović died there and was buried in Livorno, as documented in the official Italian records (Italia, Toscana, Stato Civile (Archivio di Stato), 1804–1874).

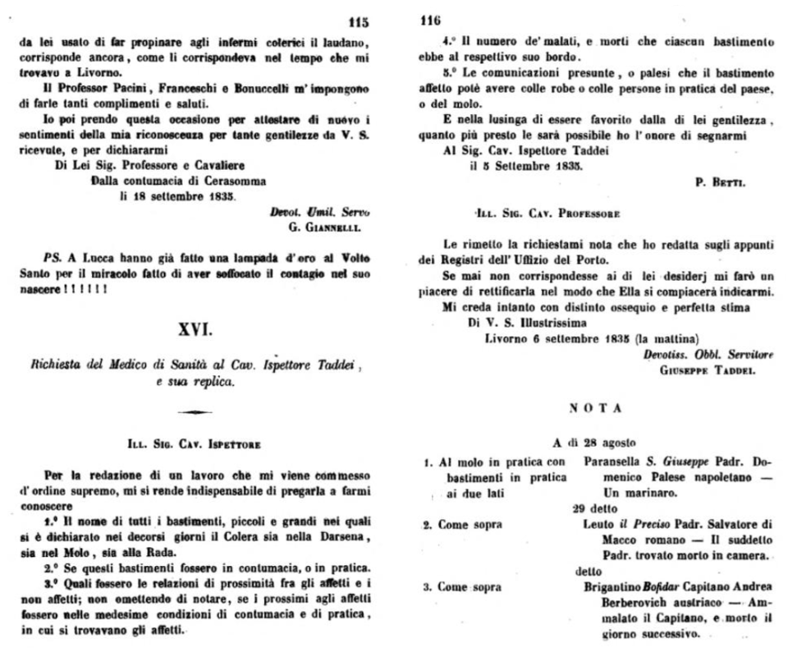

This is also confirmed in the 1857 volume by Pietro Betti, Documents appended to the considerations on Asiatic cholera, which afflicted Tuscany in the years 1835–36–37–49, published in Florence by Tipografia delle Murate, the following entry appears:

“Brig Bojdar. Captain Andrea Berberovich, Austrian — The captain fell ill and died the following day.”

This document places Captain Andrija Berberović among the maritime victims of the 1835 cholera outbreak in Tuscany, adding an important medical and historical context to his final days in Livorno.

As reported by Špiro Milinović, command of Božidar passed to his younger brother Captain Krsto Berberović.

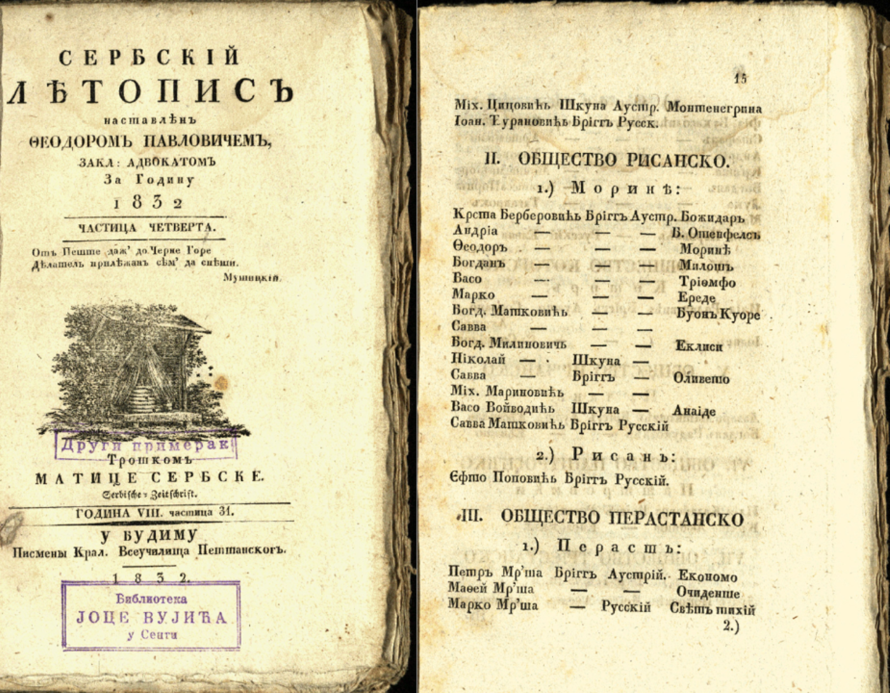

Excerpt from Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta, listing the Morinj captains of the early 19th century. The entry records Andrija Berberovich as commander of the brigantine Božidar, recalls his combat against pirate ships in the Greek archipelago aboard Felice Auguri, the loss of his left arm, the award of the Gold Medal for Bravery, and his death in Livorno (1835). (Click image to enlarge.)

Sources: Vasko Kostić, Exploits of the Boka Sailors Beyond Boka (Подвизи Бокеља ван Боке); Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta; Hrvatski biografski leksikon, “BERBEROVIĆ, Andrija”; Niko Luković, Postanak i razvitak trgovačke mornarice u Boki Kotorskoj. Beograd 1930; Gazzetta di Milano, Wednesday, 19 September 1827, “Regno Illirico”, extract from a private letter dated 7 September, reported from Trieste (14 September); Der Bote von Tyrol 20. September 1827; Österreichischer Beobachter 25. September 1827; Italia, Toscana, Stato Civile (Archivio di Stato), 1804–1874, death record (Livorno, 1835); Betti, Pietro. Documenti annessi alle considerazioni sul colera asiatico che contristò la Toscana negli anni 1835–36–37–49. Firenze: Tipografia delle Murate, 1857.

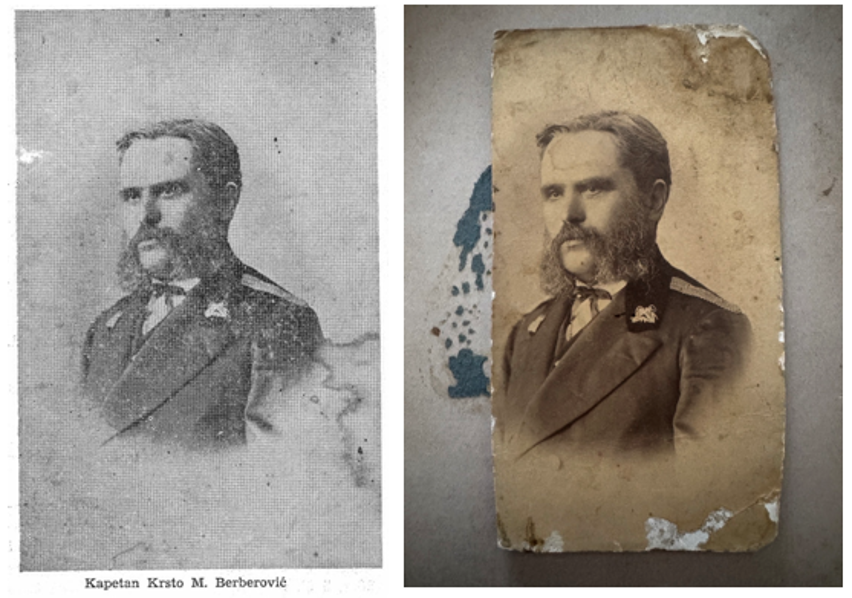

Captain Krsto Berberović, son of Đorđe (c.1795-c.1860)

The captain abandoned by pirates on a desert island

Krsto Berberović (Cristoforo Berberovich, in Italian) grew up in Morinj, the younger brother of legendary Captain Andrija Berberovich and the son of Captain Đorđe Berberovich. He sailed the exposed routes linking Trieste, Odessa, Alexandria, and the Aegean during years when safety meant very little at sea. His swashbuckling encounters with pirate ships were covered in news reports across and beyond the Habsburg Empire.

Continue reading →

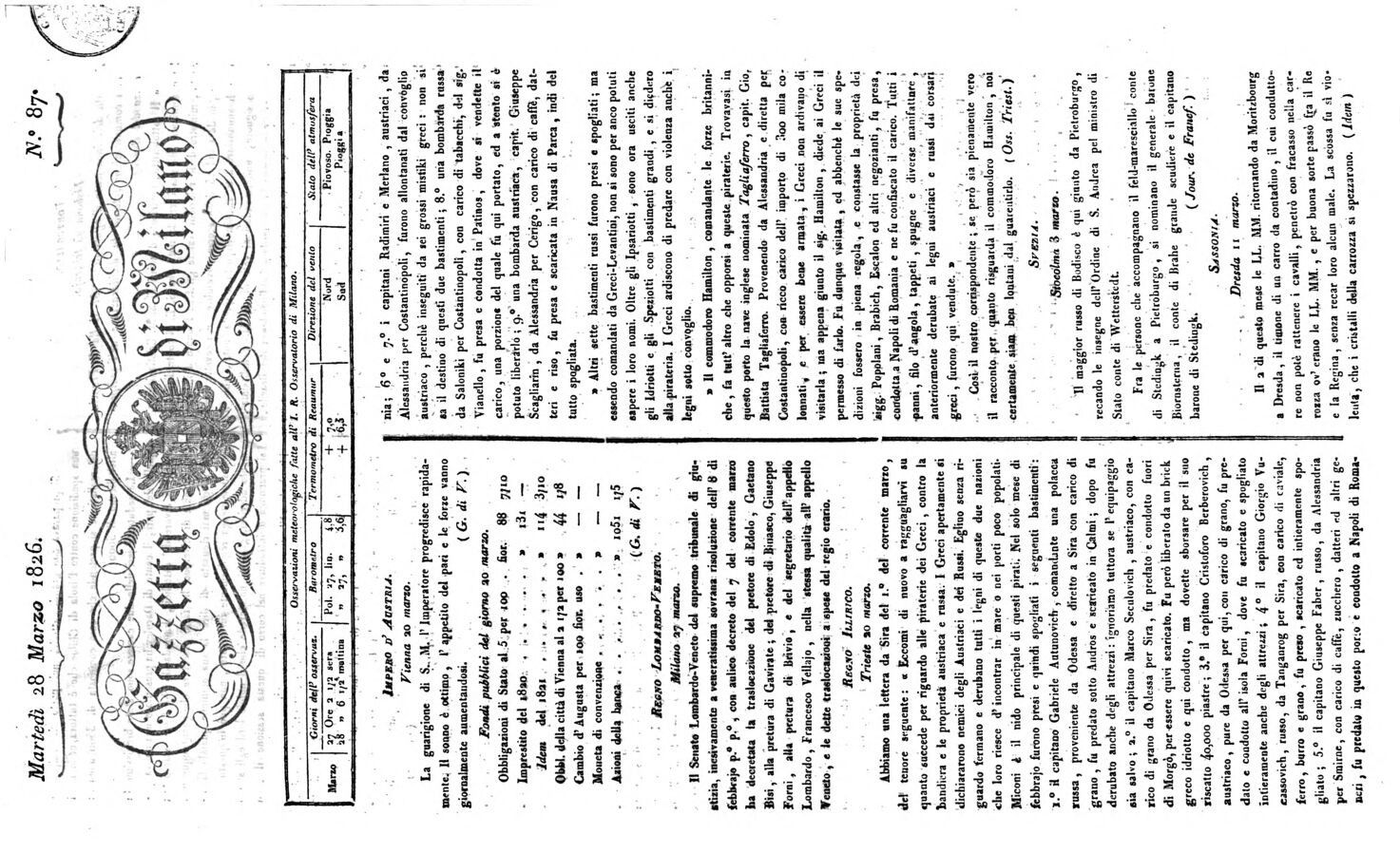

A Captain making headlines

It was by the early 1820s, that Krsto name appeared for the first time in press reports as an adventurous and resilient Austrian captain on the Odessa–Trieste grain route.

In the Gazzetta di Milano of 9 April 1824 (news from Smirne, dispatch dated 3 March 1824), we read of a ship sailing under the English flag, driven by bad weather into Sant’Andrea (Standite), where it sold its grain cargo to Captain Berberovich, who was sailing under the Austrian flag. Shortly afterward, in an unexpected turn of events, a pirate vessel entered the harbor and seized Barberovich’s ship and all its goods. The same report goes on to mention further captures of other Austrian vessels by corsairs from Casso (Kassos), making it clear that this was no isolated incident, but part of a wider pattern of piracy in those waters.

A report dated 3 March 1826 describes the Austrian brigantine Endimione, commanded by Captain Berberovich, attacked in the waters of Samos. The ship was “completely stripped of its cargo of grain” (“fu intieramente spogliato del carico di grano”) and left unable to navigate; the captain had to reach Smirne to seek assistance.

Naked on a desert island

In another Italian press report from March 1826 (Gazzetta di Milano n. 87), we read that it was Captain Cristoforo Berberovich who, sailing from Odessa under the Austrian flag, was captured by Greek pirates and taken to the islands of Fori (Fournoi Korseon), where he was left “stripped entirely, even of his tools and equipment” (“spogliato intieramente anche degli attrezzi”). Reports in German and Hungarian newspapers mention Krsto’s name again, the pirate encounter, and the fact that he had been abandoned “naked” on a deserted island.

Finally, from an article published in Der Bote von Tirol, dated 11 May 1826 (Trieste correspondence dated 3 May), we learn that an Austrian brigantine commanded by Captain Berberovich could finally reach Trieste after the captain had been detained and taken to Santorini, and that the article confirms all the cargo had been seized by the pirates.

A long maritime career

Maritime records reported by Špiro Milinović show that Krsto was very active also in 1830s, mentioning among other journeys how in 1832 aboard the brigantine S. Ludovico, carrying grain from Odessa to Rose, he could complete the journey in just twenty-two days.

After the death of his brother Andrija in Livorno (1835), command of the brigantine Božidar passed to Krsto.

Page from the Gazzetta di Milano, 28 March 1826, reporting on piracy in the Aegean. The article records the seizure of the Austrian brigantine Eudimione, commanded by Captain Cristoforo Berberovich, sailing from Odessa with a cargo of grain, and notes that he was left “spogliato intieramente anche degli attrezzi” (entirely stripped even of the ship’s equipment) on the island of Fori. (Click image to enlarge.)

Sources: Gazzetta di Milano (9 Apr 1824; Smirne dispatch 3 Mar 1824); Austrian press (3 Mar 1826; *Endimione* / Samos); Gazzetta di Milano (28 Mar 1826; Fori; “spogliato… anche degli attrezzi”); Österreichischer Beobachter, 12 June 1826 (Jahresübersicht, 1826); Der Bote von Tirol (11 May 1826; Trieste correspondence 3 May 1826); Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta.

Captain Marko Berberović, son of Petar (1793-1875) ★

Gold, corsairs, and the rise of a shipowner

Captain Marko Berberović (Marco in Italian) was considered a very remarkable man already by his contemporaries; his name appears in news reports, maritime registers, and history books. As a ship captain, he was kidnapped by Greek corsairs and had his share of pirate cannonballs; later in life, he accumulated enough wealth to co-own several ships together with the Popović shipowners of Trieste.

Continue reading →

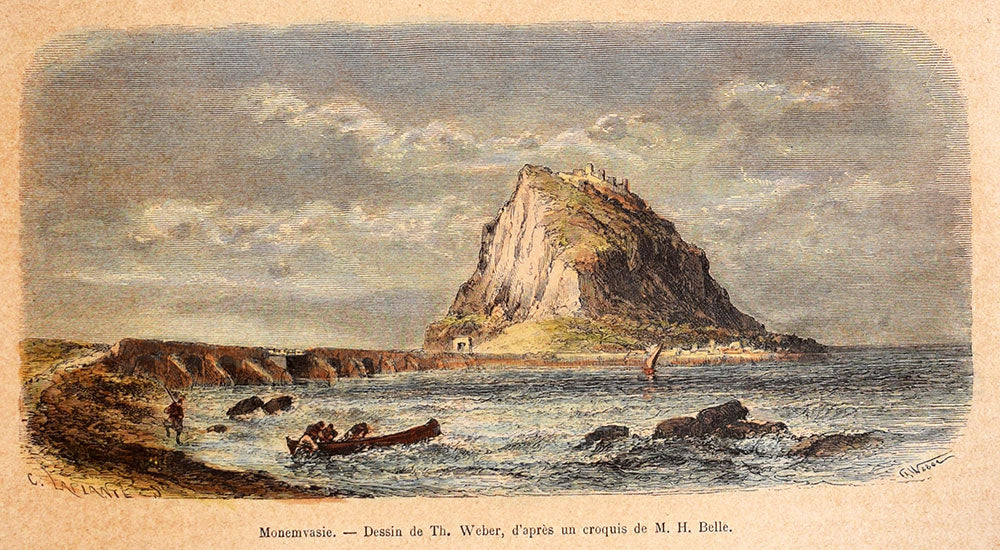

Kidnapped by pirates to Napoli di Malvasia

Marko Berberovich qualified as long-distance captain on the year of his 26th birthday, in 1819, with a decree issued by the I. R. Governo del Litorale Austro-Illirico:

It is interesting to read how, on 12 June 1826, the Viennese newspaper Österreichischer Beobachter narrated one of Captain Marko’s many encounters with Greek corsairs:

Four hundred barrels were taken from a Greek brigantine. That same night Captain Marko Berberović arrived here, who had been stopped in the waters of Cerigo (modern Kythira), taken to Napoli di Malvasia (Monemvasia, Peloponnese), and there robbed of his entire cargo intended for this place.

Of the money rolls that he had with him, and which were taken from him, the corsair captain returned one gold roll to him, so that he would not accuse the Greek sailors of betrayal, claiming that he had appropriated all the money for himself. One also speaks of other similar acts of robbery, about which no definite information has yet been obtained.

An act of bravery

In 1827, an act of bravery was reported in the Augsburger Ordinari Postzeitung von Staats-, gelehrten, historisch- und ökonomischen Neuigkeiten. The newspaper describes how Captain Marco Berberović, commanding an Austrian merchant vessel, together with four other Austrian merchant ships, encountered a corsair brig in Mediterranean waters and took part in resisting pirate attacks during a period of widespread piracy. This was also reported by the Münchener politische Zeitung and other newspapers from that year.

In the Register of ships departing from the Free Port of Trieste in 1839 (Listino dei bastimenti partiti dal Porto-Franco di Trieste nell’anno 1839), it is recorded that Captain Marko Berberović sailed with the brigantine Otaz and a cargo of grain for the harbour of Cork, in Ireland.

From captain to shipowner

Spiro Milinović reports that Captain Marko became severely ill following an injury to his leg. Once recovered, he could not take to the sea again and invested his wealth in buying quotas of several ships.

In the IsTraJ19 database managed by the University of Zadar, which includes a complete list of shipowners and captains from that time, Marko Berberović is recorded as co-owning the brig Otaz with the Popović family of Trieste as early as 1853 (the same brig he had been captain of). He is also recorded as co-owner of the brig Isgled, which was captained by his son, Captain Krsto (Cristoforo) Berberović, in 1859 and again in the years 1867–1869.

Marriage and notable children

Records of the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Dabar and Bosnia (Mitropolija dabrobosanska) show that Marko Berberović married a noble woman from Bijela, Marija Zloković, who was related to Prince (Knez) Nikola Zloković and to several notable Orthodox clerics of the Bay of Kotor, including Pop Vasilije Zloković and Proto-presbyter Simeon Zloković. Their daughter, Katarina Berberović, married Metropolitan Georgije Nikolajević, whereas Marko's son Krsto followed his father's footsteps as long-distance captains.

Second marriage and death notice

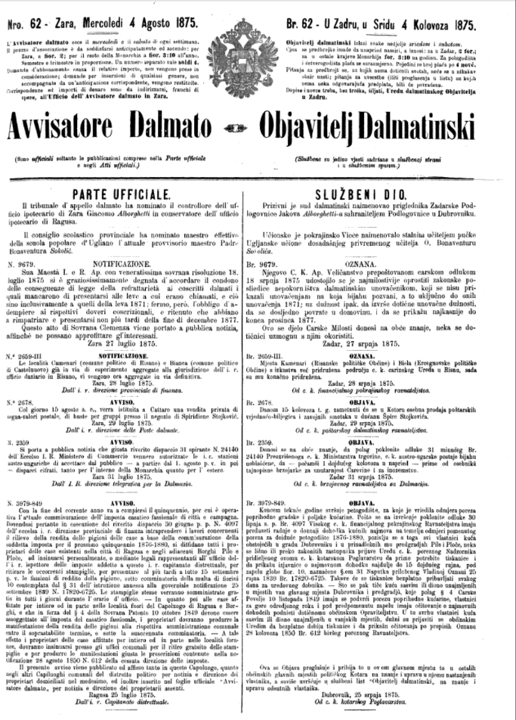

Captain Marko Berberovich passed away on 30 April 1875 in his home in Morinj. The bilingual journal Avvisatore Dalmato / Objavitelj Dalmatinski, published in Zara on 4 August 1875, reports an "Editto" which reveals a lot of interesting information about Captain Marko, which was not otherwise available.

EDITTO N. 462.

Morì intestato a Morigno nel dì 30 aprile p. p. Marco Berberovich q.m Pietro lasciando dopo di sé la superstite ved. Anastasia e l’unico figlio Cristoforo Berberovich.

Ignoto essendo l’attuale luogo di dimora del suddetto Cristoforo Berberovich, col presente lo si diffida, ad insinuare nel termine di un anno la dichiarazione d’erede a questo Giudizio sulla paterna eredità, coll’avvertimento che scorso tale termine sarà proceduto nella ventilazione ereditaria in concorso di D.n Nicolò cavaliere Berberovich deputatogli in curatore.

Risan 29 maggio 1875.

Dall’I. R. Giudizio Distrettuale.

Here the translation in English

NOTICE No. 462.

Marco Berberovich, son of the late Pietro, died intestate in Morinj on 30 April of the past year, leaving behind his surviving widow Anastasia and his only son Cristoforo Berberovich.

As the current place of residence of the said Cristoforo Berberovich is unknown, he is hereby summoned to submit, within the term of one year, a declaration of heirship before this Court regarding the paternal inheritance, with the warning that, once this term has expired, the inheritance proceedings will be carried out in his absence, together with Don Nicolò, Knight Berberovich, appointed as his curator.

Risan, 29 May 1875.

From the Imperial–Royal District Court.

Here what we learned

- at the time of his death, in 1875, Captain Marko was no longer married to Marija Zlokovic, but he had a new wife, Anastasia.

- he had only one surviving son, Captain Krsto. In fact we know from other sources that his daugther Katarina passed away in 1866 and his first born Petar died drawning in the Black sea in 1844. We do not know if Marko had some other children, but based on this Editto, only Krsto was still alive in 1875

- Krsto was not in Morinj at the time of his father death, nor he was in Morinj for several months later. Marko passed away on April 30, and the edit of May 29 was published on August 4 (edition n. 62) and once again on August 11 (edition n 64)

There is no documental information to know if all three children (Petar, Katarina and Krsto) had the same mother. It is documented that Katarina (born c.a 1813) was daughter of Marija Zokovic (Mitropolija dabrobosanska). And Petar was born before Katarina (Milinović). However, Krsto was born several years later (c.a 1829), which could suggest him to be born in the second marriage of his father Marko with Anastasia. As a supporting element, the granddaughter of Krsto (dauther of his son Milivoj) will be named Anastasia, and so was also called (as a second name) the granddaughter of Anastasia.

Sources: Österreichischer Beobachter, Vienna, 12 June 1826 (Jahresübersicht, 1826); Augsburger Ordinari Postzeitung von Staats-, gelehrten, historisch- und ökonomischen Neuigkeiten, 1827, Bericht vom 27. Februar 1827 (Bukarest), Erwähnung von Kapitän Marco Berberović im Zusammenhang mit Piraterie im östlichen Mittelmeer; Münchener politische Zeitung mit allerhöchstem Privilegium (Munich Political Gazette, published under the highest royal privilege), 1827; Gazzetta di Milano, Wednesday, 19 December 1827, “Impero Ottomano, Notizie dall'Arcipepago”; IsTraJ19, East Adriatic Sailing Ships Trade in the 19th Century – Peak and Decline (Istočnojadranska trgovina na jedrenjacima u 19. stoljeću – vrhunac i pad), University of Zadar: data collected from IsTraj19 database website www.istraj19.unizd.hr ; Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta; Mitropolija dabrobosanska (Serbian Orthodox Church), biographical article on Đorđe (Georgije) Nikolajević reporting on the marriage record and the name of the parents of Katarina, Kotor, 16 April 1833; Annuario Marittimo per l’anno 1857 VII Annata. Compilato dal Lloyd Austriaco con l’approvazione dell’eccelso I. R. Governo Centrale Marittimo. Trieste: Sezione Letterario-Artistica del Lloyd Austriaco, 1857; Avvisatore Dalmato / Objavitelj Dalmatinski. No. 62. Zara (Zadar), 4 August 1875 (Official bilingual gazette of the Imperial–Royal Dalmatian administration.)

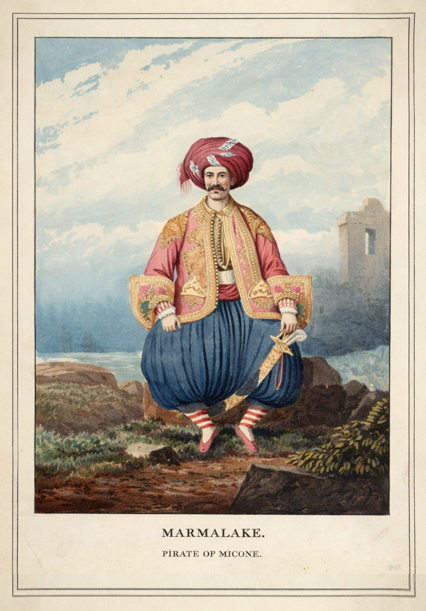

Morinj Captains in the 1832 Serbian Chronicle

In the 1832 volume of the Serbian Chronicle (Serbski Letopis / Сербскій Лѣтописъ), a register of captains from Morinj within the Risan community lists a total of 14 captains. Of these, one captain is recorded as sailing under the Imperial Russian flag, namely Savva Mašković (Савва Машковић, Brig Russkij), whereas the other 13 are sailing under the Austrian flag. Six otf them belong to the Berberović brotherhood:

- Krsto Berberović — Austrian service — brig Božidar

- Andrija Berberović — Austrian service — brig Von Ottenfels

- Teodor Berberović — Austrian service — brig Morinj

- Bogdan Berberović — Austrian service — brig Miloš

- Vaso Berberović — Austrian service — brig Triumfo

- Marko Berberović — Austrian service — brig Erede

This list does not appear to be complete, or perhaps it was not fully updated by 1832. In fact, in the port registers of Trieste for the same year, we find corresponding entries for Krsto (Cristoforo), Andrija (Andrea), and Bogdan (possibly Diodato). However, the Trieste records also list Pietro (Petar), then in command of the Morigno (Morinj), as well as Luca (Luka) and Basilio (possibly Blažo). Moreover, we know from other sources that Andrija was no longer commanding the brigantine Von Ottenfels in 1832.

This contemporary record also seems to be in contradiction with what is reported by Milinović (and indirectly confirmed by Betti in 1857), who states that Krsto Berberović took over the Božidar only in 1835 after Andrija’s death. However, the 1832 Serbian Chronicle already documents Captain Krsto Berberović as commanding the Božidar in 1832.

Reference: Сербскій Лѣтописъ (Serbian Chronicle), Part IV, Year VIII, Issue 31. Pavlović, Teodor (ed.), Buda: Royal University Press of Pest for Matica Srpska, 1832. Portata dei bastimenti arrivati nel porto-franco di Trieste l’anno 1832. Trieste: Tipografia Eredi Coletti, 1832.

See the original record →

Captain Elia Berberović

A story from the Royal Diplomatic Archives

Arduino Berlam (1880–1946) was a Triestine architect, scholar, and historian. Together with his father Ruggero Berlam, he designed the Synagogue of Trieste, inaugurated in 1912 — one of the largest synagogues in Europe and a major architectural landmark of the city.

In his book La colonia greca in Trieste ed i suoi addentellati con la guerra d’indipendenza ellenica (1821–1830), Arduino Berlam recounts the following episode concerning Captain Elia Berberović, which he found in a large archival file entitled “Seeräubern”, preserved in the Royal Diplomatic Archive in Trieste:

See the original record →

A pirate attack on the "Sovrano d'Austria"

On 11 June 1825, Captain Elia Berberovich, commander of the brigantine “Sovrano d’Austria”, appeared before the Imperial and Royal Consulate of Smyrna, where he reported that, near Chios, he had suffered an attack by Greek corsairs, who by force seized several packages of the cargo and many fittings and effects of the vessel.

The Captain shouted at them to move away, but instead they drew closer and boarded the vessel from the stern, about fifty armed men entering the deck at once. Rushing immediately toward the helm, they forced the ship toward the coast of Chios. The threats made by the commanding captain — warning them that they were insulting the glorious Austrian flag and that they were not permitted to board — proved useless. They replied that they were corsairs and that they must act as corsairs; they told the Captain that there were Turks and their merchandise aboard his brigantine. The Captain replied that he had neither Turks nor their goods. Irritated by this response, they assaulted the hatchway, removed the new hawser, and began removing the packages of merchandise and loading them onto their own small vessels.

When the Captain and the Clerk opposed these acts of violence, they were forcibly pushed to remain at the stern and were not even allowed to take note of what was being carried away. While some plundered the hold, others in the cabin opened the smaller packages and took whatever pleased them most. They also carried away property belonging to the Captain himself: a telescopic blunderbuss, two pistols, three mouthpieces, and from his chest about seven hundred Turkish piastres, as well as various other utensils. When the Captain, who was at the stern, opposed the plundering of the cabin, one of the armed Greeks threatened to kill him with a pistol he held in his hands, and he was forced to withdraw.

Once they had finished plundering the hold and the cabin at their pleasure, they went below and opened all the sailors’ chests. In that of the boatswain Spiridione Berberovich they found money. When they attempted to take it, he resisted, but one of the Greeks drew his knife to kill him. As the boatswain parried the blow, it struck another Greek, who was wounded in the arm. At that moment one of their leaders arrived, reproached them, restored calm, and compelled them to go up on deck and to leave the money to the said boatswain. Then, at about nine in the morning, after loading onto their own vessels whatever best pleased them, they abandoned the brigantine in the greatest disorder, embarking onto their own craft.

The Greek colony of Trieste

The purpose of Berlam’s study is to demonstrate that the Greek colony of Trieste was not a marginal or purely commercial diaspora, but an active participant in a wider Mediterranean network connecting Trieste, the Ionian Islands, the Aegean, Constantinople, and Odessa.

By documenting shipping routes, captains, merchants, consular records, and episodes of piracy and privateering, the book shows how Trieste functioned as a strategic hub where economic activity, religious affiliation, and political movements intersected. In this sense, the work is fundamental for understanding Trieste not only as an imperial port of the Habsburg Empire, but also as a city deeply embedded in the political transformations of the eastern Mediterranean in the early nineteenth century.

Italian censorship

In April 1941, Berlam’s book was censored by the Italian government. This occurred during World War II, at a time when Italy was militarily and politically involved in the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean. In this context, a historical study addressing the Greek War of Independence, Greek nationalism, and the transnational role of Greek communities in the port of Trieste was considered politically sensitive.

The decision to excise the text reflects the broader system of wartime cultural control exercised by the Ministero della Cultura Popolare, aimed at regulating the circulation of historical interpretations deemed unsuitable under contemporary political circumstances.

The book was eventually published in Trieste in 1946 by the Stabilimento d’Arti Grafiche L. Smolars & Nipote.

Sources: Arduino Berlam, La colonia greca in Trieste ed i suoi addentellati con la guerra d’indipendenza ellenica (1821–1830), Stabilimento d’Arti Grafiche L. Smolars & Nipote (Trieste, 1946)

Captain Blažo Berberović, son of Petar

Blažo Berberović, Captain Marko’s brother, qualified as a long-distance captain in 1819, on the year of his 26th birthday, by decree of the I. R. Governo del Litorale Austro-Illirico. Although less is known about his career than about Marko’s, the records show that he initially shared command of the same brigs, Erede and Otac.

See the original record →

In the maritime registers of the 1850s, Captain Blažo Berberović appears as commander of the ships Marijeta and Gregorius (equipped with 6 cannons), both vessels with a tonnage exceeding 500 tons. In particular, in the 1857 Annuario marittimo, Biagio (Blažo) is listed as domiciled in both Trieste and Lepetane, and includes a record of repairs he commissioned for his ship Gregorius.

Sources: Annuario Marittimo per l’anno 1857 VII Annata. Compilato dal Lloyd Austriaco con l’approvazione dell’eccelso I. R. Governo Centrale Marittimo. Trieste: Sezione Letterario-Artistica del Lloyd Austriaco, 1857; Avvisatore Dalmato / Objavitelj Dalmatinski. No. 62. Zara (Zadar), 4 August 1875 (Official bilingual gazette of the Imperial–Royal Dalmatian administration.); Annuario marittimo per l’anno 1859, Lloyd Austriaco, IX annata, Trieste, Sezione Lett.-Artistica del Lloyd Austriaco, 1859.

Captain Tripo Berberović, son of Petar (1800-1873)

Captain Tripo Berberović, younger brother of Marko and Blažo, shared the command of the ship Marijeta with Blažo

Katarina Nikolajević, née Berberović (c.1813–c.1866)

The incredible life and legacy of Katarina Berberović

At the international conference “Migration from Antiquity to the Present Day”, held in Novi Sad in April 2018, Professor Irena Arsić of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš, presented a paper on the exceptional lives of three Dubrovnik women of the 19th century. One of the three protagonists was Katarina Nikolajević, née Berberović, daughter of the merchant, shipowner, and sea Captain Marko Berberović from the Bay of Kotor.

Katarina (in some documentary evidence referred to as “Ekaterina”, or familiarly as “Kata”) will enter history as the wife of Georgije (Đorđe) Nikolajević (1807–1896), a Serbian cleric, theologian, writer, and professor, who later became Metropolitan of Dabar-Bosna and led an extraordinary life, extensively documented in books and online sources.

Far less has been written about his wife, Katarina Berberović.

Continue reading →

Katarina was born in Morinj, around 1813, the second child of Marko Berberović (who had yet to start fighting pirates) and Marija Zloković. Her older brother, Petar, died by drowning in the waters of the Black Sea on a journey to Odessa, whereas her younger brother Krsto, would become a prominent ship captain, following the family tradition.

A combined marriage and the move to Dubrovnik

As reported by Dimitrije Ruvаrac in the biography of Metropolitan Nikolajević (1898), and confirmed by a recent publication by Bojanić & Vasić (2025), Katarina Berberović moved to Dubrovnik in 1833, shortly after her marriage to Đorđe (Georgije) Nikolajević.

Đorđe Nikolajević had in fact arrived in Dubrovnik earlier. At the request of the Serbian Orthodox Church Municipality, the Metropolitan of Karlovci, Stefan Stratimirović, sent him in 1829 to open a school and teach Orthodox children. Traveling via Trieste (Vučković 1897), Đorđe reached Dubrovnik in December 1829 (Bojanić & Vasić, 2025). The school, however, operated for only a short time and was soon closed by the authorities, who claimed that the teacher was a “cleric” and threatened him with expulsion (Vučković 1897).

After it was officially established that Nikolajević was a layman, the city authorities allowed him, at the end of 1830, to teach privately “in homes”, providing elementary education and religious instruction to Orthodox children in Dubrovnik. In this restrictive context, and in order to secure a lasting institutional presence for Orthodox education, Metropolitan Rajačić later devised a solution: to ordain Nikolajević as a secular (married) priest, which would allow him to act simultaneously as parish priest and teacher (Bojanić & Vasić, 2025).

For this purpose, it was necessary that Nikolajević find a wife and form a family. Eventually, the choice fell on Katarina: a member of the Berberović family, an old lineage of priests and sea captains, firmly Orthodox and strongly Serbian in identity.

From maternal side, Katarina was no less remarkable. Her mother, Marija Zloković, was born into a noble priestly family from Bijela, another important center in Boka Kotorska, whose history is well documented in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Members of the Zloković family served as Orthodox parish priests and senior clergy, including Pop Vasilije Zloković, attested in the late eighteenth century, and Proto-presbyter Simeon Zloković, who in the early nineteenth century exercised ecclesiastical authority over a wide area of the Bay of Kotor. The most notable ancestor of Marija and Katarina, however, was a prince: Knez Nikola Zloković, active at the turn of the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, who combined princely authority with military service and later - as in the Bokelj tradition - held the rank of Captain.

Đorđe Nikolajević married Katarina Berberović on 16 April 1833 in Kotor. According to the official biography published by the Serbian Orthodox Church, the wedding ceremony was officiated by prota Jakov Popović. Shortly after the marriage, Nikolajević was ordained deacon and then priest (Ruvarec 1898), becoming in November 1833 the first secular parish priest in Dubrovnik, where he soon reopened a school (catechesis) and remained active as parish priest and teacher until 1858.

This sequence of events — from Nikolajević’s arrival in Dubrovnik in 1829 to his marriage and ordination in 1833 — is clearly documented and well synthesised in the study by Bojanić and Vasić (2025).

Life under surveillance

After their arrival in Dubrovnik, Đorđe Nikolajević’s activities were numerous: he organized the parish, built the church, founded a school, and edited the only Serbian-language journal then published in Dalmatia, the Magazzino Serbo-Dalmata. As a result, the household of Nikolajević and Katarina Berberović was placed under constant surveillance by the authorities.

Life for the Serbian community in Dubrovnik at that time was neither easy nor safe. Katarina shared a hard, dangerous, and uncertain life with the Orthodox parish priest of Dubrovnik. How unjustly their family situation was neglected—despite Nikolajević’s extraordinary achievements—is shown by a letter he sent to Vuk Karadžić (Irena Arsić, private communication, 2025), asking for help in securing an apprenticeship in Vienna for their son Čedomil. All indications suggest that this attempt was unsuccessful. In the letter, Nikolajević wrote:

“My son Čedomil, who is about to turn thirteen, has completed here all the regular schools… and now attends the second class of the gymnasium; he has also learned to read and write in German… Both he and I have an unspeakable, truly inexpressible desire to enter commerce. If this desire is not fulfilled for us through your intercession and your excellent friends, then you may consider us both as sad and miserable.”

Recognition and family tragedy

It was only in 1849 that, by a ministerial decision, the Austrian government recognized the Orthodox faith in Dalmatia as one of the legally acknowledged confessions, on the basis of which many Orthodox Serbs in Dalmatia returned to Orthodoxy. Nevertheless, the situation in Dubrovnik remained unsafe for the Serbian-speaking community.

Đorđe and Katarina worked tirelessly to maintain peace and harmony in the community, and to remain faithful to Austrian rule. This effort was eventually recognised by His Majesty the Emperor and King Franz Joseph I, who, by decree of 7 July 1850, awarded Đorđe the Golden Cross of Merit (no medal for Katarina, though).

In 1850, Prota Đorđe and his wife Katarina suffered a great loss: on 2 February 1850, their only son Čedomil died, in the seventeenth year of his young life, and on 20 May 1850 their daughter Sofija, aged fourteen.

In the words of Dimitrije Ruvаrac in his 1898 biography:

“What kind of father Prota Đorđe was, and how deeply the death of his children struck him, can be seen from the booklet Čedomil Nikolajević, Posthumous Crown, by his sister Sofija Nikolajević, and from several of his friends, with poems printed in Dubrovnik in 1850.”

Journey, expulsion, and later years

Left alone, without children (“whom they had loved and cherished as the light of their eyes”, in the words of Dimitrije Ruvаrac), friends advised Katarina and Đorđe to leave Dubrovnik for a while and take a journey.

From Dubrovnik, in the autumn of that year, they set out through Zadar, Gračac, Zagreb, Petrinja, and Sisak, and then on to Srem to Đorđe’s relatives, where they remained for three months, seeking consolation. From there they continued through Sremska Mitrovica to Belgrade, where he spent several days, staying with various acquaintances and paying visits to prominent figures: Vuk Karadžić, Petar Petrović, Ilija Garašanin, and Jovan Gavrilović, who received him with imperial honours.

Đorđe then visited the monastery of Grgeteg, where Archimandrite Arsenije Stojković was then abbot. They received him as a guest and showed him their monastic brotherhood. There is no record of where Katarina stayed during this visit to Grgeteg; it is plausible to assume that she remained in Belgrade.

After those three months, they returned the same route—through Novi Sad, Zemun, Vienna, Ljubljana, and Trieste—back to Dubrovnik, where the people received them warmly and joyfully.

However, a few years later, in 1858, the Nikolajević family was, in effect, expelled from Dubrovnik, accused of having assisted the rebels of Luka Vukalović. In despair, Prota Đorđe Nikolajević even appealed to the imperial family, but received no assistance (Irena Arsić, private communication, 2025).

Prota Đorđe Nikolajević received an appointment as professor in Zadar, and Katarina followed him, leaving Dubrovnik behind.

On 10 March 1866, Prota Đorđe Nikolajević suffered a family tragedy that struck him deeply. On that day, after a long and severe illness, his faithful and good wife Katarina died in her 58th year, and thus Prota Đorđe was left alone. He himself fell into various illnesses, sought medical help, but could not recover for long time.

Several students of the Orthodox seminary, priests, and writers at that time wrote him letters of condolence, moved by the sorrow of the aged Prota Đorđe.

Knowing how deeply his wife, until her death, had grieved for their late children, and how she had repeatedly visited their graves in Dubrovnik, weeping over them and easing her sorrow, Prota Đorđe—after obtaining permission from both ecclesiastical and secular authorities—had her remains transferred in 1875 from Zadar to Dubrovnik, to the family grave where their children had already been laid to rest.

In loving memory of his wife Katarina Berberović, Prota Đorđe Nikolajević established several scholarships to support the education of young Serbian women in Dalmatia and the formation of teachers in the Bay of Kotor area. One of these scholarships was established with the explicit request to prioritize children of the Berberović family.

Within this legacy, the youngest brother of Katarina, Captain Krsto Berberović, sent his son Milivoj (Michele in Italian), born in 1861, to study at the Istituto Magistrale in Zara in 1875, to become a teacher. Milivoj did in fact become a teacher, taught at the primary school in Morinj, and later moved to Trieste, where he became a teacher at the Serbian school and—for some years—also the director of the Serbian school in Trieste.

Prota Đorđe Nikolajević ended his life and career as Metropolitan of Dabar-Bosna in Sarajevo, where he died in 1895.

Sources: Irena Arsić of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš, “Three Dubrovnik (Ragusa) women of the 19th century: Katarina Nikolajević (c. 1813–c. 1851), Vasilija Lainović (1824–1895), Teodora Bošković (1835–1895)”, International Scientific Conference Migration from antiquity to the present day, Novi Sad, Serbia, 14-15 April 2018;

Irena Arsić, Private Communication 2025: (О трима Дубровкињама XIX века), in Serbian;

Ruvаrac, Protojerej Dimitrije. Biography of Metropolitan Đorđe Nikolajević of Dabar-Bosnia (Životopis mitropolita Đorđa Nikolajevića, dabro-bosanskog) (Животопис митрополита Ђорђа Николајевића, дабро-босанског). Zemun: Jova Karamata Printing House, 1898;

Vučković, Jovan. 1897. Biografski zapisi o Đorđu (Georgiju) Nikolajeviću. Zadar, str. 58–59;

Bojanić, Snežana; Vasić, Dejana. “The significance of the work of Metropolitan Georgije Nikolajević for the study of Serbian medieval studies.” Church Studies 22 (2025): 443–456.

Gavrilović, Andra (1903). Famous Serbs of the 19th Century, Year II. Serbian Printing House. pp. 53–54;

Mitropolija dabrobosanska, „Đorđe (Georgije) Nikolajević – biografija“, zvanični sajt Srpske pravoslavne crkve; podatak o braku sa Katarinom (Ekaterinom), kćerkom Marka Berberovića i Marije rođ. Zloković, vjenčanje u Kotoru 16. aprila 1833, uz službu prote Jakova Popovića.

Pop Spiridon Berberović (c.1795-c.1850)

Spiridon Berberović is recorded as an Orthodox priest from Morinj ordained and appointed in 1805. This reference appears in archival material published and analysed by Ljubo Mačić in his study on churches, monasteries, and clergy in the Bay of Kotor during the period of French rule (1807–1813), based on documents preserved in ecclesiastical and state archives.

Continue reading →

The information derives from archival documentation related to the organisation of Orthodox parishes in the Bay of Kotor at the turn of the 19th century. Following the French assumption of authority over the region, administrative and ecclesiastical arrangements were restructured. On the basis of decisions taken in 1807 by the French military and civil administration, the Bay of Kotor was reorganised into three administrative districts: Kotor, Herceg Novi, and Budva. A central delegate represented royal authority in Kotor, while the other two districts were overseen by subordinate officials. As part of these reforms, the previous ecclesiastical authority exercised by the Cetinje metropolitans over the Orthodox population of the Bay was brought to an end (Ljubo Mačić, based on French administrative records).

The French authorities maintained a detailed bureaucratic approach to governance, producing systematic records of population, taxation, property, churches, monasteries, and clergy. Much of this material has been preserved in the Archive of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Kotor, with additional documentation held in the Historical Archive of Kotor. Within this administrative context, and at the request of the General Governor of the Illyrian Provinces, a comprehensive survey of churches and clerical personnel was ordered. In response, Archimandrite Gerasim Zelić, acting as deputy for the Bay of Kotor, submitted a detailed report dated 30 December 1811, providing structured information on parishes, priests, and ecclesiastical jurisdictions across the region. This report confirms the existence of a well-defined parish network in which Morinj occupied a clearly documented place.

Quoting from Ljubo Mačić, Arhivski podaci o crkvama, manastirima i sveštenstvu u Boki Kotorskoj u vrijeme francuske vladavine (1807–1813):

Morinj

The parishes belonged to the following churches: St John, St Thomas, St Petka, and St Elijah. Parts of the parish were Kostanjica, Strp, Lipci, and Lepetane. The number of believers was 1,060, and the parish priest was Bogdan Milinović, aged 42. He was supported by the parishioners, and the annual income in grain and wine amounted to 200 francs.

In the already mentioned list of ordained and appointed priests, Spiridon Berberović is recorded, Morinj, 1805.

Spiridon is also documented as serving as the parish priest in Morinj in 1833 and as the father of Proto Nikola Berberović. In fact, contemporary ecclesiastical writing on Njegoš’s visit to Kotor in 1833 records Pop Spiridion and his son in the accounts of the visit (Nikolić, in Istorijski zapisi)

References:

Ljubo Mačić, “Arhivski podaci o crkvama, manastirima i sveštenstvu u Boki Kotorskoj u vrijeme francuske vladavine (1807–1813)”.

Marko S. Nikolić, “Petar II Petrović Njegoš i protoprezviter kotorski Jakov Popović. Povodom Njegoševe posjete Kotoru 1833. g.”

(„Петар II Петровић Његош и протопрезвитер которски Јаков Поповић“, „Поводом Његошеве посјете Котору 1833. г.“),

Istorijski zapisi, p. 466.

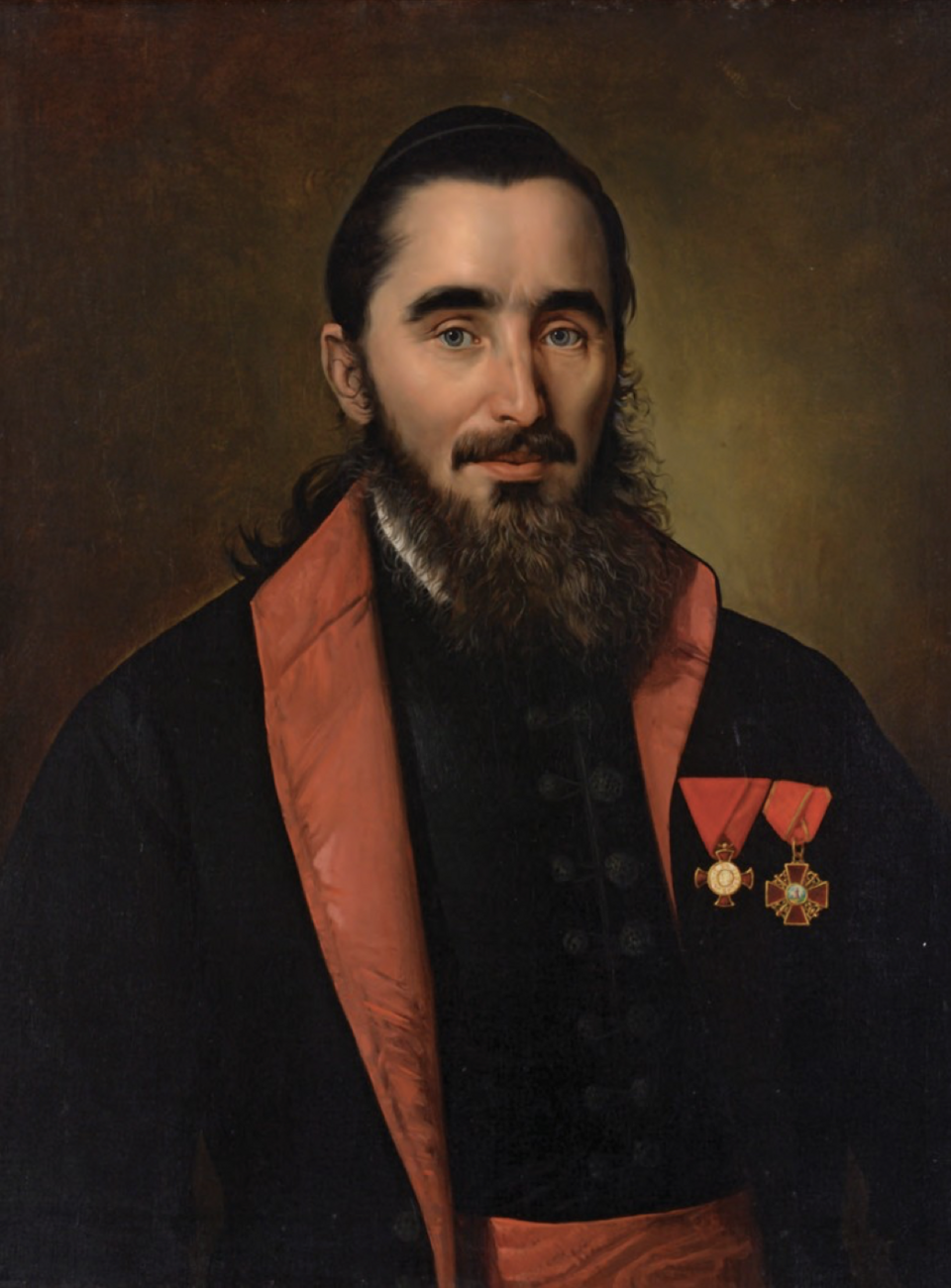

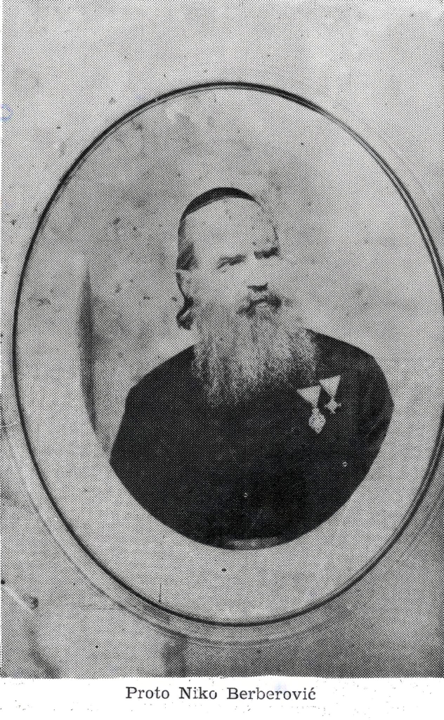

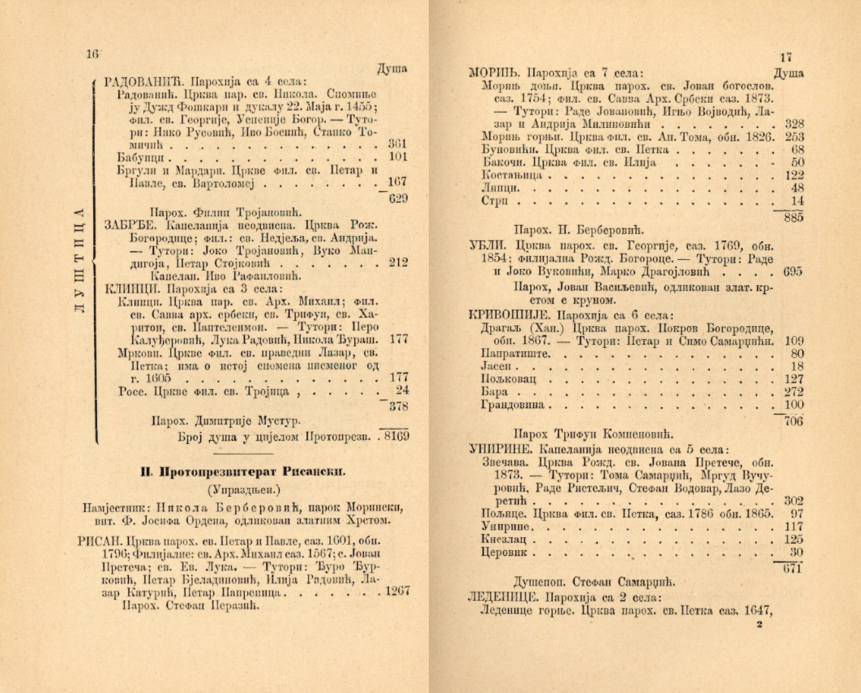

Proto Nikola Berberović, son of Spiridion (1820–1877)

Priest, poet, and witness of Njegoš’s legacy

Nikola Berberović, born in Morinj, Boka Kotorska, on 6 May 1820, was the son of Pop Spiridion Berberović, who served as the Orthodox parish priest of Morinj and other settlements in the Bay of Kotor.

Unlike the other members of the Berberović family encountered so far, Pop Nikola did not fight pirates. Nevertheless, he played a key role in pacifying the Krivošije Uprising of 1869, triggered by the introduction of mandatory military conscription in the Bay of Kotor. For this service, in 1870 he was appointed Knight of the Imperial Austrian Order of Franz Joseph.

Continue reading →

Nikola received his basic education at the local school in Risan and partly at the Italian elementary school in Kotor. He later attended the so-called “Greek Catholic” (that is, Orthodox) theological schools in Šibenik and Zadar. After completing his studies, he served in the parishes of Ubli and Morinj and for a period acted as supervisor of public schools in the Risan district.

In an article on the life of Krile Matov Milinović (the benefactor who established the Morinj school), Jovica Vukasović reports that Krile’s sister Vasa Milinović was married to Pop Nikola Berberović, described as a respected parish priest of Morinj and a close personal friend of Krile Milinović himself. The same article notes another remarkable relationship: Nikola’s close friendship with Metropolitan Petar II Petrović Njegoš, a central figure of Serbian Orthodox culture. Njegoš was Prince-Bishop (Vladika) of Montenegro, as well as a poet and philosopher whose works are considered among the most important in Montenegrin and Serbian literature.

This personal connection is supported by contemporary ecclesiastical sources, as reported by Marko S. Nikolić in his contribution to Istorijski zapisi. The first encounter between Nikola and Njegoš took place during Njegoš’s visit to Boka Kotorska in 1833, when Nikola was thirteen years old and living in the household of his father, Pop Spiridion Berberović, then parish priest of Morinj. Both Spiridion Berberović and his son are mentioned in accounts of the visit, and Nikolić explicitly notes how Nikola would later engage with Njegoš’s legacy in his literary work.

Indeed, Pop Nikola’s early writings focused on ethnographic descriptions of folk customs, published in the Serbo-Dalmatian Magazine (Srpsko-dalmatinski magazin). His later work evolved toward poetry strongly influenced by Njegoš’s The Mountain Wreath (Gorski vijenac, „Горски вијенац“).

Nikola Berberović’s principal work is the poetry collection Prvo-rodna kći (Firstborn Daughter) („Прво-родна кћи“), printed in Zadar in 1855. The collection is of particular historical importance for a poem written on Njegoš’s death, which preserves Njegoš’s burial wish (amanet) in verse. A copy of the original 1855 edition is today held by the City Library and Reading Room of Herceg Novi, as recorded in the COBISS public library catalogue. An early edition of Gorski vijenac (not the first edition) has been part of the private collection of the Bevilacqua/Berberović family for several generations.

Original:

No kad umrem, to dobro da znate,

na Lovćen me tamo ukopajte,

da bi s kostim tamo počinuo,

jer sam za to crkvu ogradio.English translation:

And when I die, know this well:

bury me there on Lovćen,

so that with my bones I may rest there,

for I enclosed the church for that purpose.

The Serbian character of the Bay of Kotor

Another poem reflecting Nikola’s love for his homeland was cited by Lazo Kostić in his 1961 book on the Serbian character of the Bay of Kotor.

“One warm-hearted Bokelj, Nikola Berberović from Morinj, printed in Zadar in 1855, using old Serbian orthography, a piece of ‘original poetry’ under the title ‘Primordial Book.’ In the poem ‘Bokelj Wreath’, the following two verses are found:

Дакле, свак се пази домовине,

И ја моју љубим од истине!‘Therefore, let everyone guard their homeland,

And I love mine in truth!’

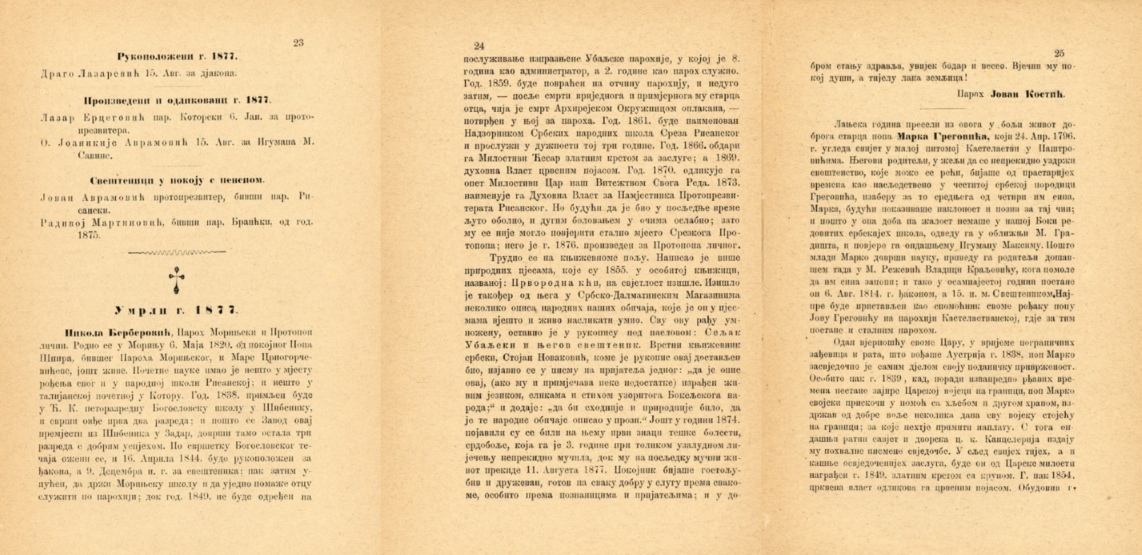

Proto Nikola Berberović died in Morinj on 11 August 1877.

See more documents →

Translation of the biographical notice by Jovan Kostić (1878)

Nikola Berberović, parish priest of Morinj and Archpriest.

He was born in Morinj on 6 May 1820, to the late Pop Špiro, former parish priest of Morinj, and Mare, née Crnogorčević, both deceased. He received his elementary education partly in the local school in Risan, and partly in the Italian elementary school in Kotor. In 1838, he was admitted to the Greek Catholic (Orthodox) Theological School in Šibenik, where he completed the first two grades; afterward, he was transferred from Šibenik to Zadar, where he completed the remaining three grades with excellent success.

After completing theological studies, he married on 16 April 1844. He was ordained deacon, and on 9 December of the same year, he was ordained priest. He was then appointed to serve at the Morinj school, and at the same time to assist his father in performing parish duties. In 1849, he was officially appointed to the parish.

He carried out his service in the Ubli parish, where he served eight years as administrator and two years as parish priest. In 1859, he was returned to his former parish, where shortly afterward he suffered the painful and premature death of his elderly father, whose passing was mourned by the Archpriestly District, and he was buried at the new parish cemetery.

In 1861, he was appointed Supervisor of Serbian public schools of the Risan district, in which capacity he served for three years. In 1866, His Grace the Emperor awarded him the Golden Cross for merit, and in 1869 the Ecclesiastical Authority decorated him with the church decoration. In 1870, His Grace our Emperor again honored him with the Knight’s insignia of his Order. In 1873, the Ecclesiastical Authority appointed him Deputy Archpriest of the Risan district.

However, as he had in recent years been severely ill, and as prolonged illness had weakened his eyesight, he could no longer perform the duties of Archpriest of Risan; therefore, in 1876, he was promoted to the rank of personal Archpriest.

He labored diligently in the literary field. He wrote several scholarly articles, which he published in 1855 in a separate booklet entitled “The First Parish, a Worldly Institution.” He also published several descriptions of our Serbian–Dalmatian folk customs, which he vividly and faithfully recorded from direct experience. All his literary work, however, he left in manuscript form under the title “The Peasant in the Ubli Region and His Priest.”

The eminent Serbian writer Stojan Novaković, to whom this manuscript had been entrusted, wrote privately to a friend: “Although this description is written by someone who, in my opinion, lacks refined literary expression, language, images, and style worthy of the Boka coastal people,” and he adds, “it would nevertheless be appropriate and useful for him to describe folk customs in prose.”

In 1874, signs of severe illness appeared, particularly a chest disease, which afflicted him for three years, during which time his painful life gradually faded. He finally passed away on 11 August 1877. Until his death, he remained hospitable and sociable, always ready to perform good deeds for everyone, especially toward acquaintances and friends; and in all respects of firm health, always kind and cheerful. Eternal peace to his soul, and may the earth lie lightly upon his body!

Parish priest Jovan Kostić

Sources: Serbian Encyclopedia, entry „Берберовић, Никола“ (Srpska enciklopedija), vol. I/2, 2011; Jovica Vukasović, Krile Matov Milinović – “A lover of enlightenment” and benefactor of Morinj („Криле Матов Милиновић – ‘љубитељ просвјешченија’ и морињски добротвор“) Boka: A Collection of Works in Science, Culture and Art, UDC 371.2.929 Milinović K.M.; Nikolić, Marko S. “Petar II Petrović Njegoš i protoprezviter kotorski Jakov Popović. Povodom Njegoševe posjete Kotoru 1833. g.” Istorijski zapisi, p. 466 Petar II Petrović Njegoš and the Kotor proto-presbyter Jakov Popović („Петар II Петровић Његош и протопрезвитер которски Јаков Поповић“), „Поводом Његошеве посјете Котору 1833. г.“; Špiro Milinović, Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta (1974); COBISS record for Prvo-rodna kći, Zadar, 1855 (Nikola Berberović); Kostić, Lazo M. O srpskom karakteru Boke Kotorske. Cirih, 1961. (Original Serbian Cyrillic edition.); Schematism of the Orthodox Diocese of Boka Kotorska, Dubrovnik, and Spič (Шематизам Православне епархије бококоторске, дубровачке и спичанске, 1874–1912).

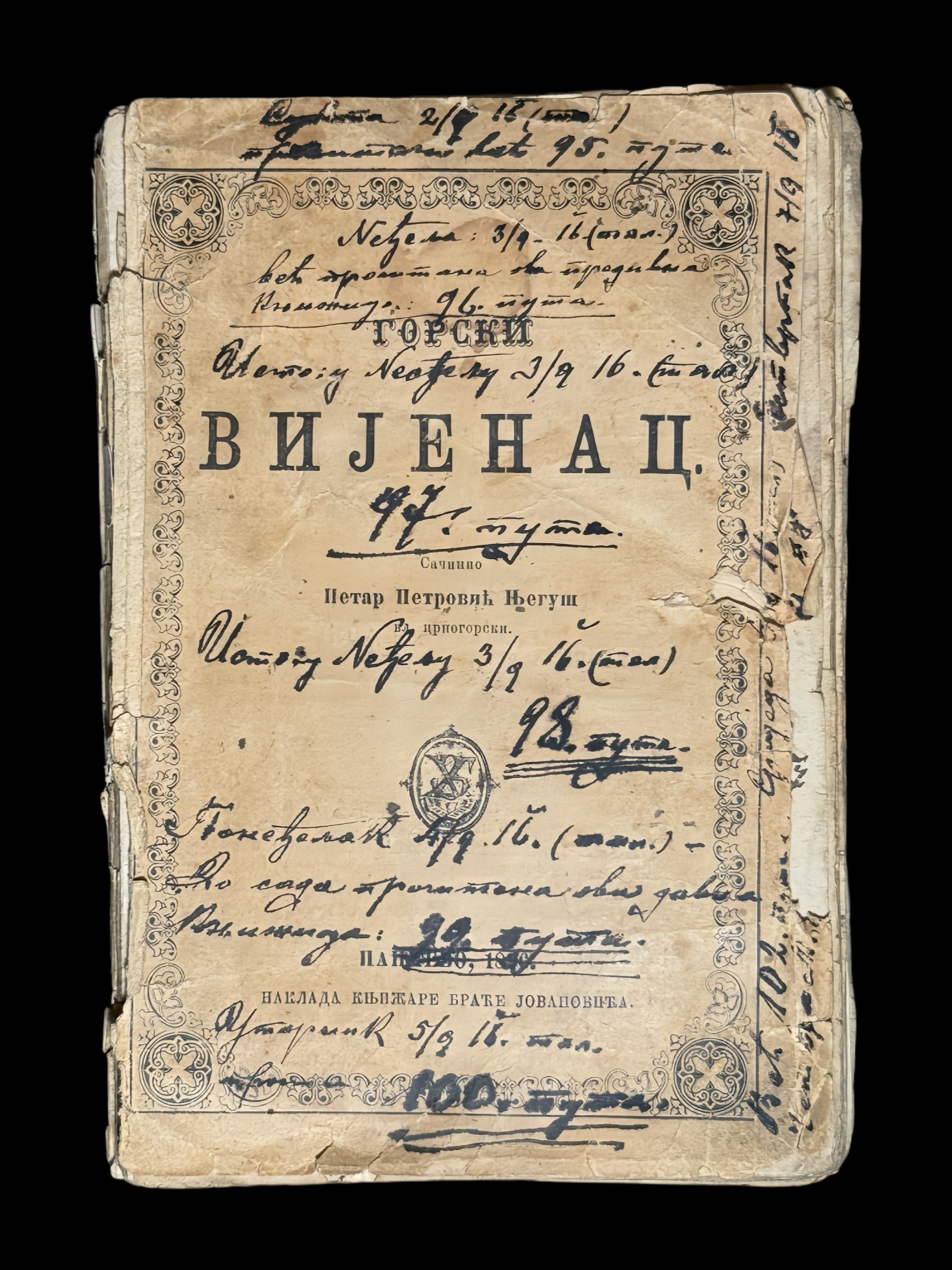

A family copy of The Mountain Wreath

Repeated readings during war and exile (1916–1917)

The Mountain Wreath (Gorski vijenac, Горски вијенац) by Metropolitan Petar II Petrović Njegoš. Braco Jovanović edition, Pančevo, 1882. Private collection.

Continue reading →

This copy of The Mountain Wreath by Metropolitan Petar II Petrović Njegoš, printed in Pančevo in 1882, is of particular interest due to numerous handwritten annotations on its inner pages, signed “М. Берберовић” (M. Berberović) and dated between 1916–1917.

The notes record with striking precision the number of times the book was read. Among the entries are those dated 19 September 1916, marking the 120th reading, followed the next day, 20 September 1916, as the 121st reading.

The reasons for this repeated rereading are unknown. No family members who could have explained the annotations were still alive when the book was rediscovered decades later in forgotten Berberović family boxes in Trieste.

At the time the notes were written, Captain Marko Berberović was serving as a naval officer of the Imperial Russian Navy in Odessa. Together with his wife, Ana Dabović, he found himself first caught in the First World War and soon after in the events leading to the Russian Revolution. As a foreign captain, he was compelled into service patrolling the Black Sea.

One hypothesis is that, under conditions of war, isolation, and uncertainty, repeated reading of a work so closely connected to family history and clerical tradition may have accompanied this period. The long-standing relationship between the Berberović family and Metropolitan Petar II Petrović Njegoš — particularly through the priest Nikola (Niko) Berberović — gives this object a continuity that spans generations.

A second hypothesis concerns the identity of the annotator. The initials “М. Берберовић” could refer not only to Marko, but also to Milivoj (Michele) Berberović. Milivoj died in early November 1918 in Trieste, a victim of the Spanish influenza.

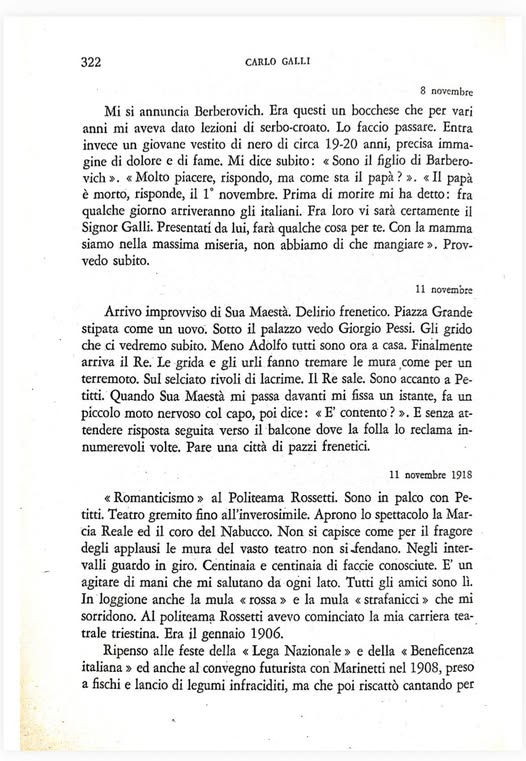

The final months of the war, coinciding with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had a severe impact on the Berberović family in Trieste. As recorded by Consul Carlo Galli in his diaries, following a meeting with Milivoj’s son, the family was described as financially ruined.

It is therefore possible that the annotations were made not in Odessa, but in Trieste, during the war years. In this reading, the repeated entries dated 1916–1917 would belong to a period marked by material hardship, illness, and the progressive disintegration of the world in which the family had lived.

This volume thus remains an ambiguous but powerful object. It is a physical trace of the Berberović family’s history, linking its priestly roots in Boka Kotorska with its maritime and urban trajectories between the Adriatic, Trieste, and the Black Sea. Passed across generations, it preserves a continuity of language, culture, and Orthodox tradition without revealing the full circumstances under which it was most intensely read.

The role of the Berberović in the Krivošije uprising (1869–1870)

After the Bay of Kotor (Bocche di Cattaro) was incorporated into the Austrian Empire, and later into the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, its population remained exempt from military conscription for several decades. When imperial authorities moved to enforce compulsory service in 1869, resistance emerged in the mountainous hinterland of the Bocche, particularly in Krivošije and Župa, developing into what contemporary newspapers described as the Krivošije uprising.

Continue reading →

62 Viennese inches for 62 kreuzer a day

Months before open fighting was reported, newspapers indicate that imperial authorities were already strengthening internal security in the southern provinces. An issue of Der Kamerad: österreichisch-ungarische Wehr-Zeitung dated 8 April 1869 published a call for the recruitment of new gendarmes from among former soldiers, reservists, and militiamen. The notice specified that applicants had to be Austrian citizens, aged 24 to 36, unmarried or widowers without children, in good physical health, and of strong build, with a minimum height of 62 Viennese inches (approximately 1.63 m). The ability to read and write and to speak a local language was required, together with good conduct, a solid reputation, and what the notice termed a “blameless previous life”, meaning the absence of prior involvement in rebellion or unrest.

The position offered a defined compensation: a daily wage of 62 kreuzer, a monthly allowance of 30 florins, and a one-time payment of 60 florins for initial equipment (Der Kamerad, 8 April 1869).

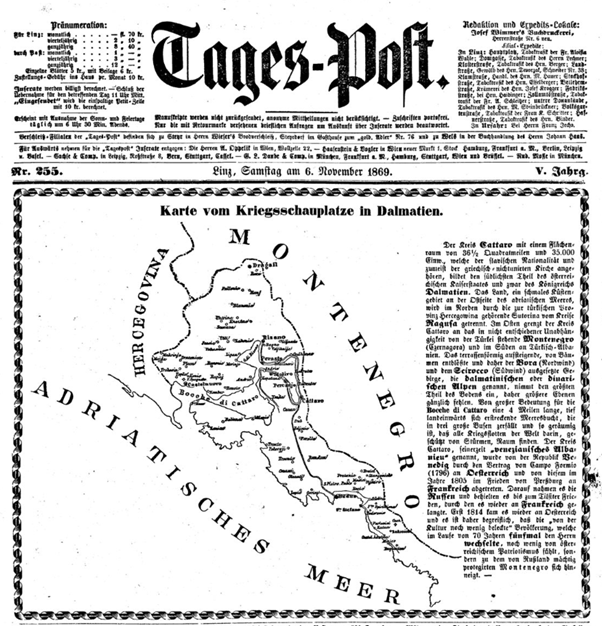

The Bay of Kotor once again on a war map!

Since the end of the Greek rebellion, the Bay of Kotor enjoyed a period of relative peace. For the past thirty years, the only news reports from the Bay were limited to the names of Bokeli captains in Austrian Lloyd’s records and registers. The Krivošije uprising put the Bay back on the map.

A detailed geographical article published together with a map of the theatre of war described the District of Cattaro as a mountainous region with a predominantly Slavic and Greek-Orthodox population, bordered by Montenegro and characterised by difficult terrain (Linzer Tages-Post, 6 November 1869). The same report noted that these lands had passed repeatedly from one sovereign power to another, a circumstance explicitly mentioned in the newspaper as shaping a strong local sense of belonging. The accompanying map identified Risano, Morinj, Castelnuovo, Dragalj, and the surrounding highlands, situating the uprising within the wider Adriatic–Montenegrin border zone.

Escalation and fighting (October–November 1869)

From late October onward, newspapers reported intense and dispersed fighting. Die Vedette (10 November 1869) described Risano as having suddenly acquired military importance and identified Morinj as a key point where access roads converged, linking Castelnuovo and Ubli with the interior and the Župa region.

Military movements involving Morinj recur in several reports. On 19 October, Austrian forces planned a demonstration against Morinj to prevent the unification of insurgent groups between Crkvice and Dragalj, supported by artillery, sailors, and gendarmes (Die Vedette, 20 November 1869). This presence of gendarmes corresponds to the earlier recruitment measures reported in April (Der Kamerad, 8 April 1869).

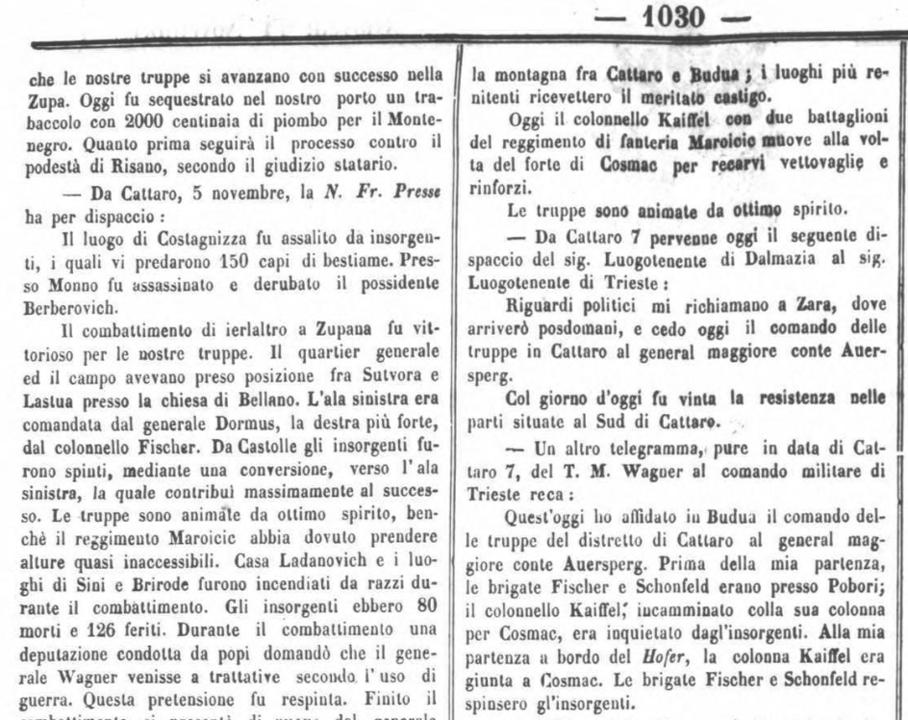

A Berberović shot dead by the insurgents

Several newspapers reported violence against civilian property and individuals. A dispatch from Cattaro dated 5 November 1869 stated that insurgents overran Costagnizza near Risano, seized livestock, and shot the landowner Berberović (Linzer Tages-Post, 6 November 1869). The same report appeared, with minor variations, in numerous newspapers across the empire between 6 and 9 November 1869, including Viennese, Styrian, Tyrolean, Carinthian, and Dalmatian papers. None of them reported the first name of this member of the Berberović family.

The spread of the uprising and the role of Montenegro

Reports from mid-November onward describe insurgents retreating into the mountains, movements near Dragalj, Stanjevići, Ubli, and continued military operations (Gemeinde-Zeitung, 11 November 1869; Das Vaterland, 22 December 1869). Naval bombardments along the coast between Morinj and Risano are also reported in December (Das Vaterland, 22 December 1869).

An article published in Die Presse. Abendblatt (Vienna, 27 December 1869) focused on southern Dalmatia and named several individuals described as agitators or leaders associated with the uprising, among them a Krsto Berberović from Morinj, listed alongside figures from Krivošije, Ledenice, and Pobori.

Click here ("Continue reading") if you want to find out if this insurgent was our Captain Krsto Berberović.Continue reading →

The wherabaouts of Captain Krsto Berberović in 1869-1870

Was this Krsto Berberović the same Captain Krsto, son of Captain Marko and brother of Katarina Nikolajević? The contemporary news reports do not state a patronymic. However, it is possible to cross-check the dates of the uprising with the well-documented travel records recorded by Špiro Milinović in Podaci o istoriji Morinja i okolnih mjesta.

These records show that in June 1869 Captain Krsto was caught in a severe storm south of Sardinia, which damaged part of the cargo. About one month later, his presence is recorded in Spanish waters. In October 1869, he returned briefly to the Bay of Kotor, where his ship remained for about a week at the anchorage near Herceg Novi (Castelnuovo). On 17 October 1869, Captain Krsto arrived with his ship in the port of Trieste. The next available record dates to February 1870, when Captain Krsto is again documented as commanding a ship under the Austrian flag.

Given this timeline, and despite the temptation to speculate, it appears highly unlikely that Captain Krsto could have left Trieste at the end of October, travelled back to the Bay of Kotor, emerged as a leader of an insurrection in which a member of his own family was robbed and shot, and then reappeared a few months later in February 1870 in command of an Austrian vessel, as if nothing had occurred.

It should also be noted that the name “Berberović” as an alleged insurgent leader appears in only a single newspaper report, and no additional independent sources confirming this attribution have been identified so far.

The question therefore remains open: who was this Krsto Berberović of Morinj who briefly emerged as an alleged insurgent leader in late 1869?

Suppression, amnesty, and later recognition

By late November and December 1869, newspapers reported that large-scale fighting had subsided, although patrols and demonstrations continued (Gemeinde-Zeitung, 11 November 1869; Das Vaterland, 22 December 1869). Subsequent reports indicate that the uprising did not result in a permanent imposition of conscription in Krivošije and that participants were eventually granted an amnesty, restoring the earlier exemption.

In August 1870, Viennese newspapers reported that His Majesty the Emperor, by decree dated 14 August 1870, conferred honours for meritorious patriotic and loyal cooperation during the suppression of the uprising. Among the recipients was Nikola Berberović, Greek-Oriental parish priest in Morinj, who received the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph (Fremden-Blatt, 20 August 1870).

The Berberović mentioned in newspaper reports on the Krivošije uprising

| Date | Name | Role as reported | Locality | Newspaper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–6 Nov 1869 | Berberović (first name not given) | Landowner shot during insurgent attack | Costagnizza / Risano area | (Linzer) Tages-Post, 6 Nov 1869 (and parallel reports) |

| 27 Dec 1869 | Krsto Berberović (likely not the Captain) | Named among alleged insurgent leaders / agitators | Morinj | Die Presse. Abendblatt, 27 Dec 1869 |

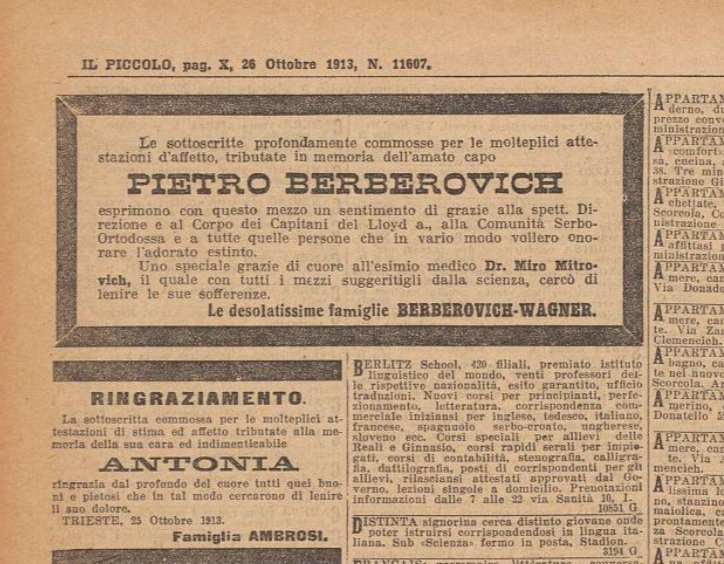

| 20 Aug 1870 | Nikola Berberović | Greek-Oriental parish priest; recipient of imperial honour for his pacifying role | Morinj | Fremden-Blatt, 20 Aug 1870 |